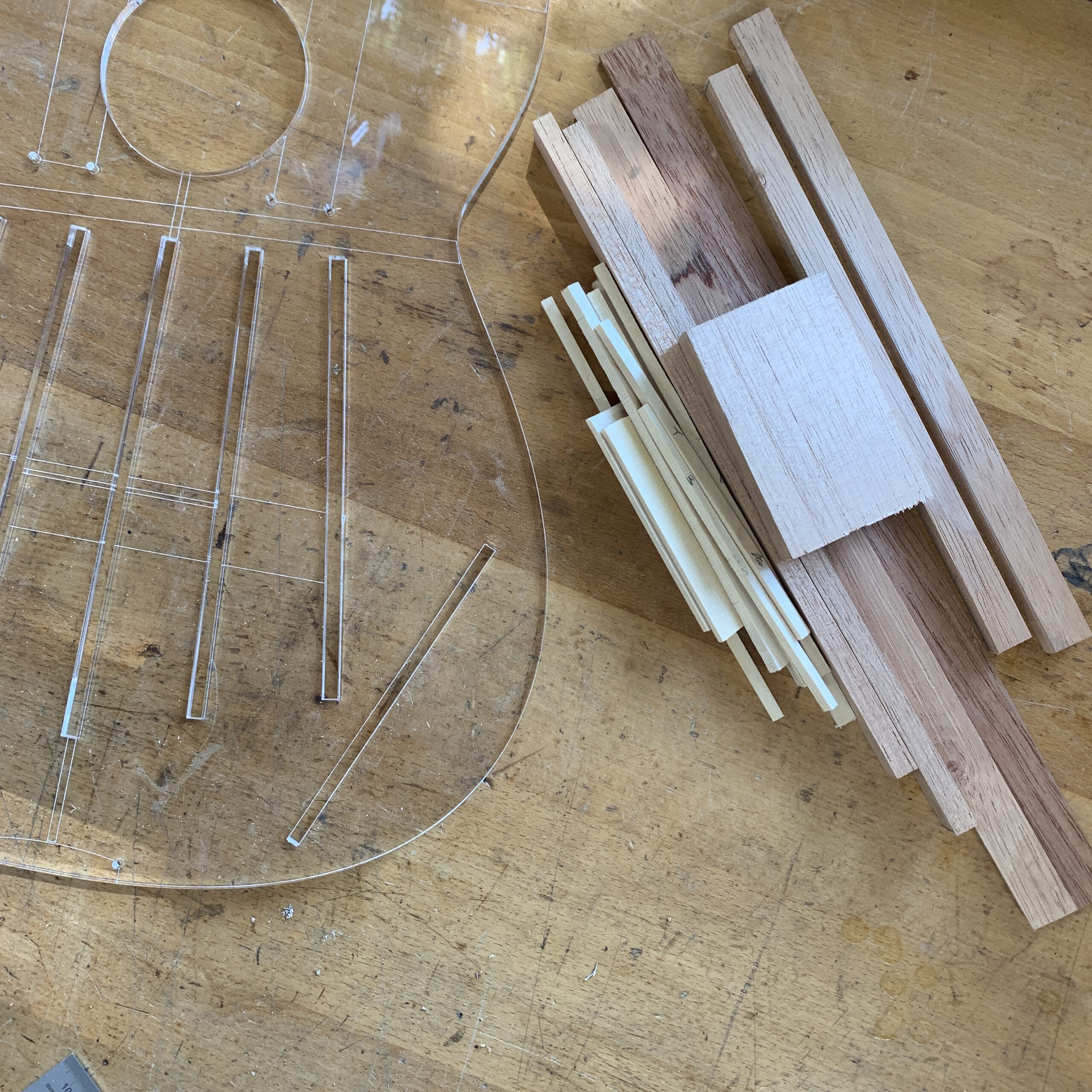

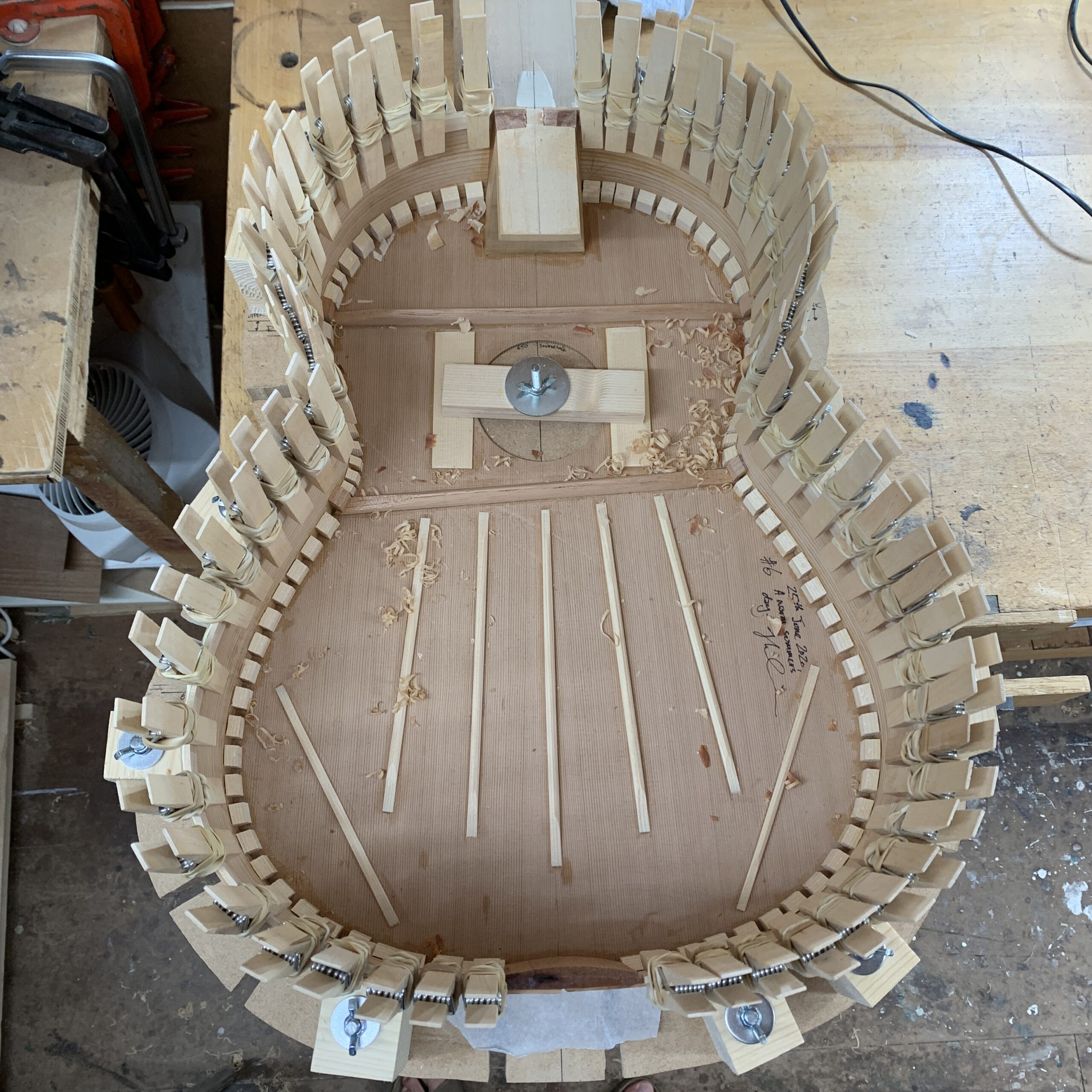

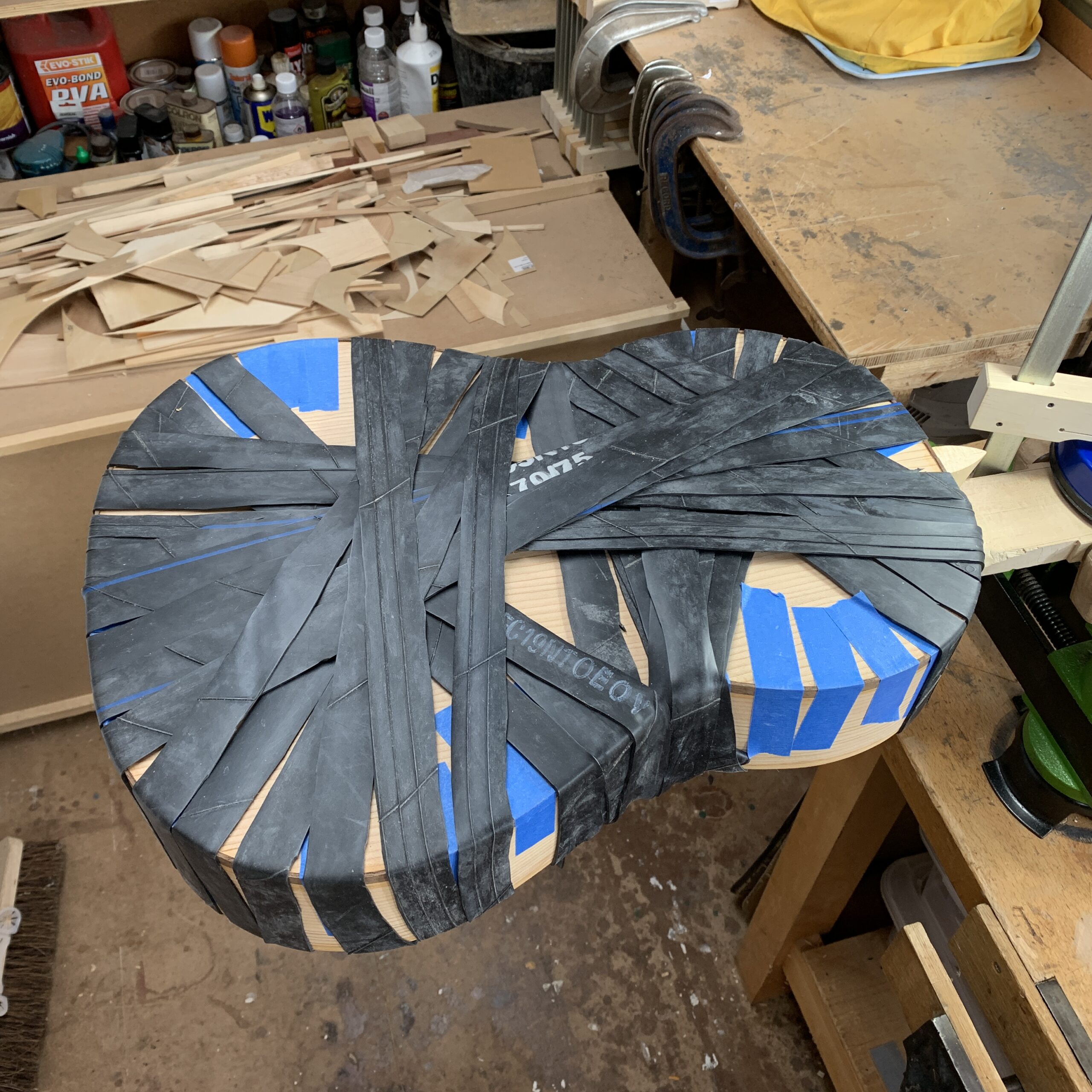

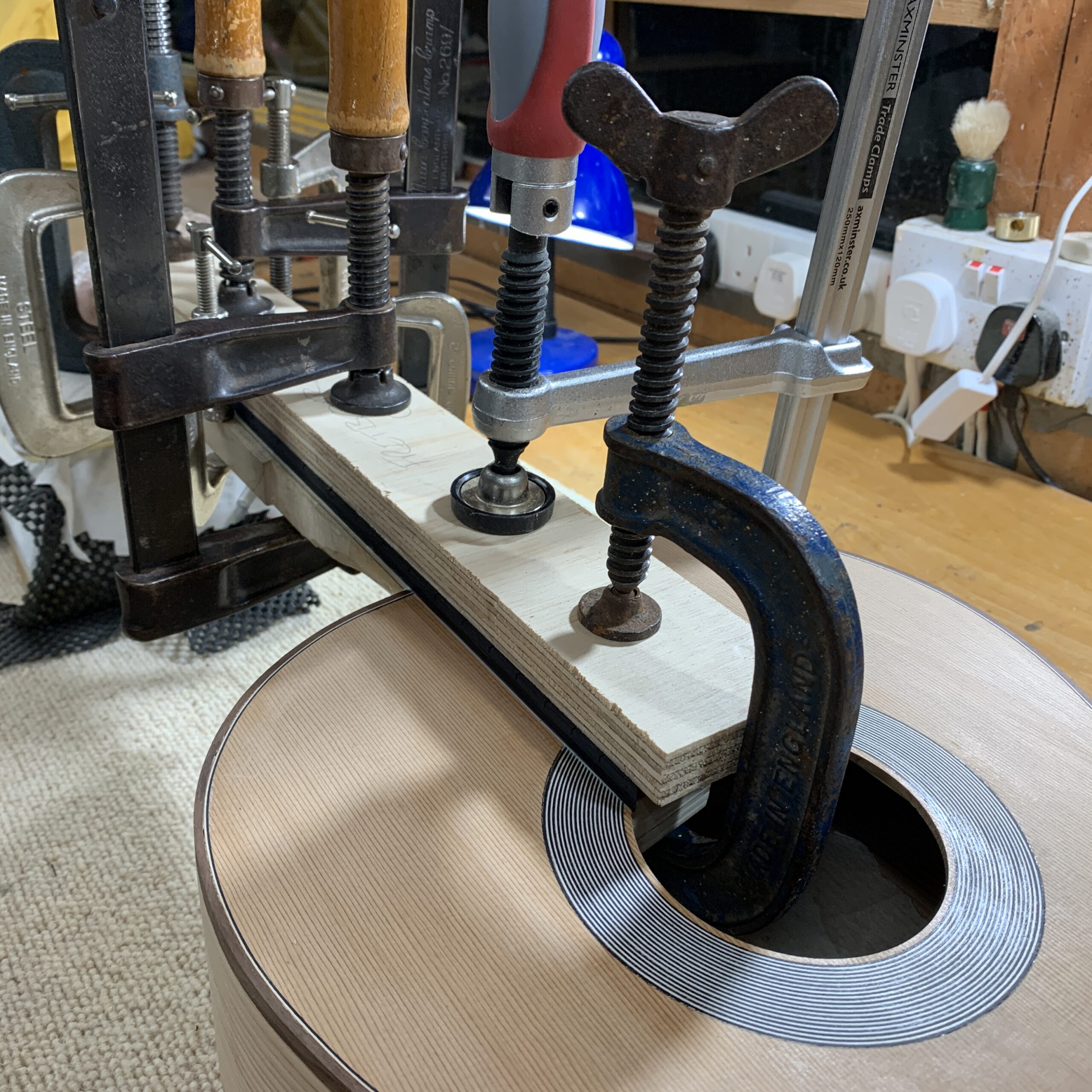

My latest guitar follows a similar lightweight design to the previous four, only this time I chose to use different tonewoods and opted for a slotted headstock. The soundboard is Western Red Cedar; back and sides of Cedar of Lebanon; a Bog Oak fretboard; Lime neck; and Walnut bridge, binding and head veneer.

The following recordings are unrehearsed pieces taken with my phone, played by Rob Johns. The strings are D’Addario EJ45 normal tension.

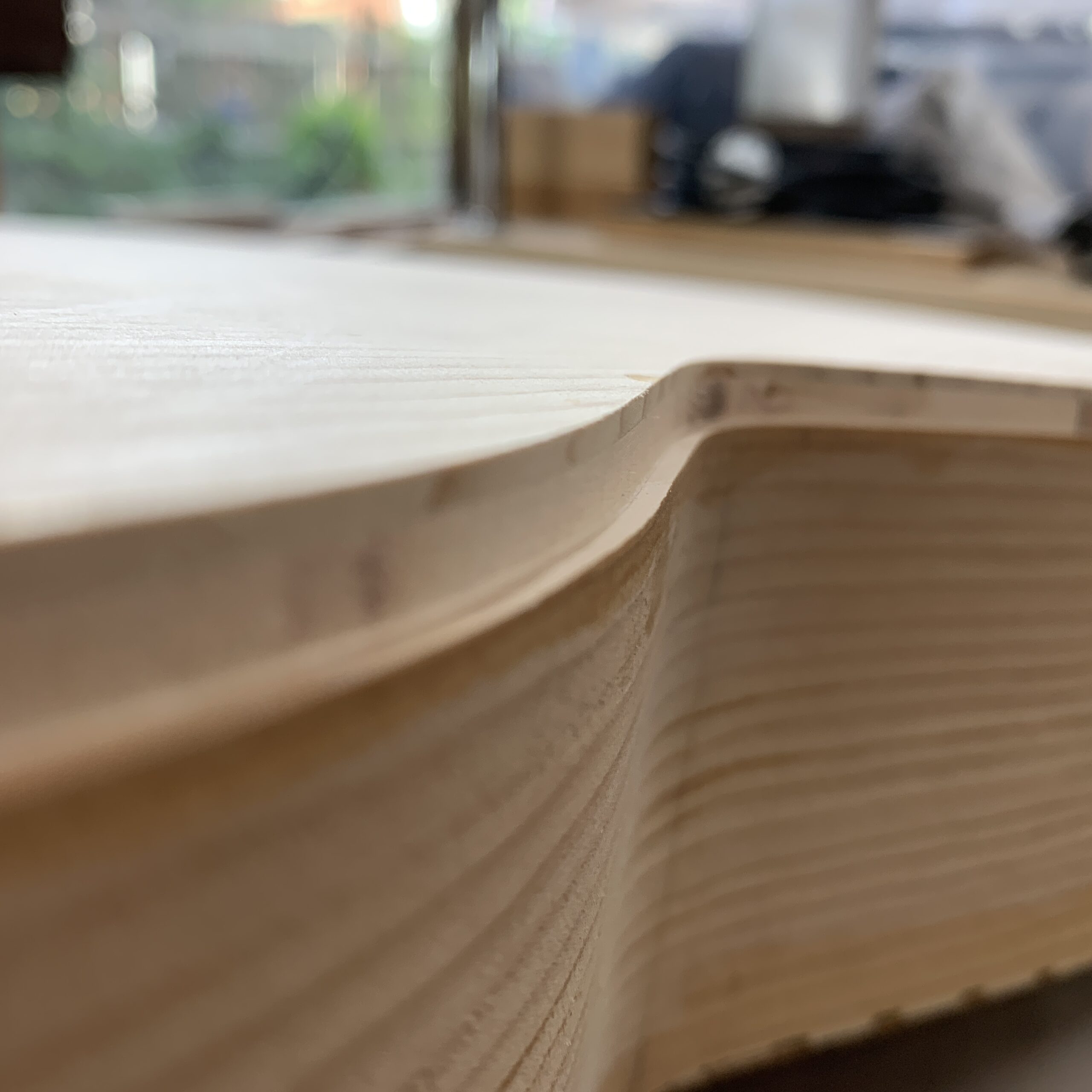

I especially enjoyed working with Cedar of Lebanon, Walnut and Lime. The Cedar of Lebanon is very similar to Cypress, the traditional wood for flamenco guitars. The density of my set is 503 kg/m3 and I thinned the back and sides to about 2mm. It bends well and has an amazing fragrance – not the same as Cypress but just as appealing and the colour is a close match, too.

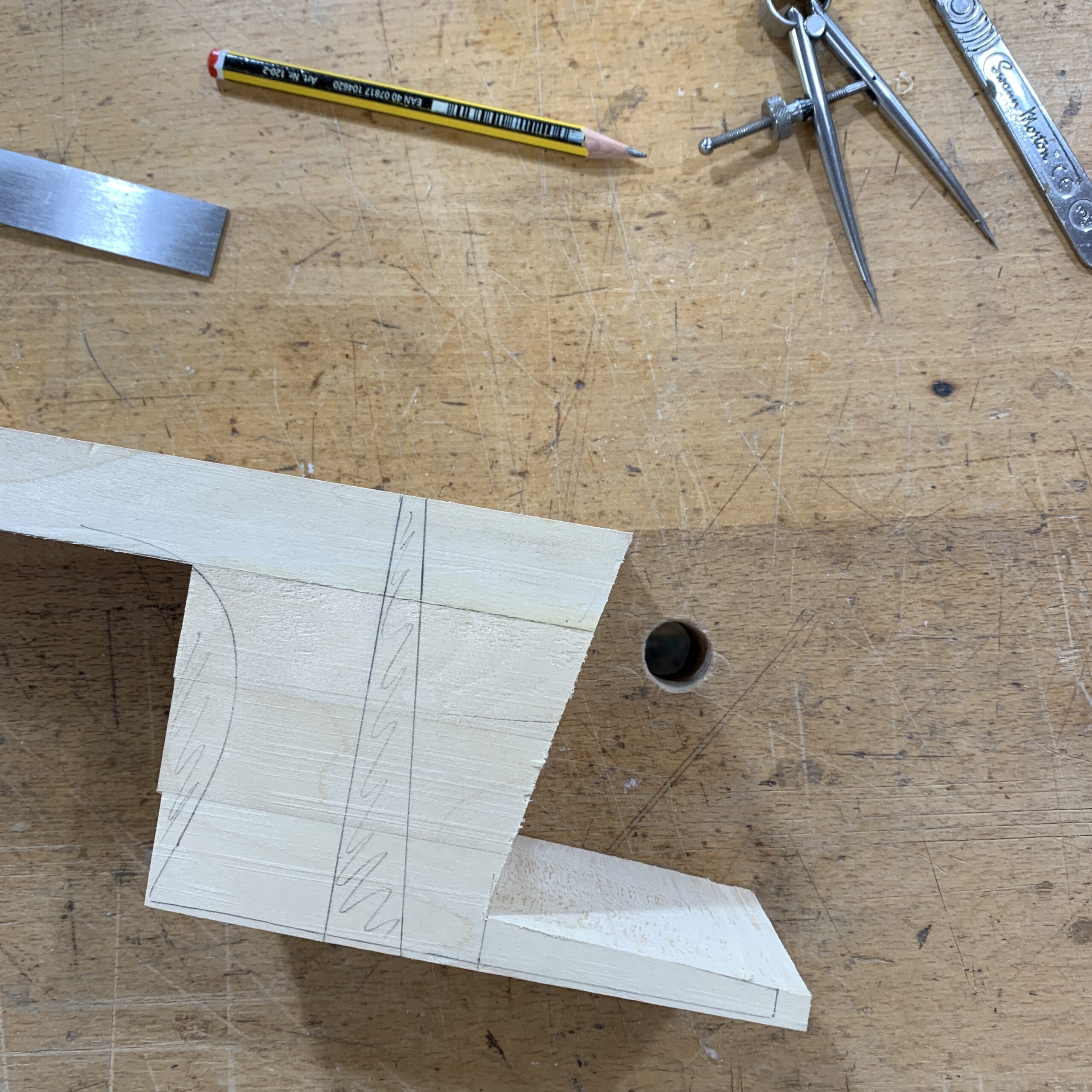

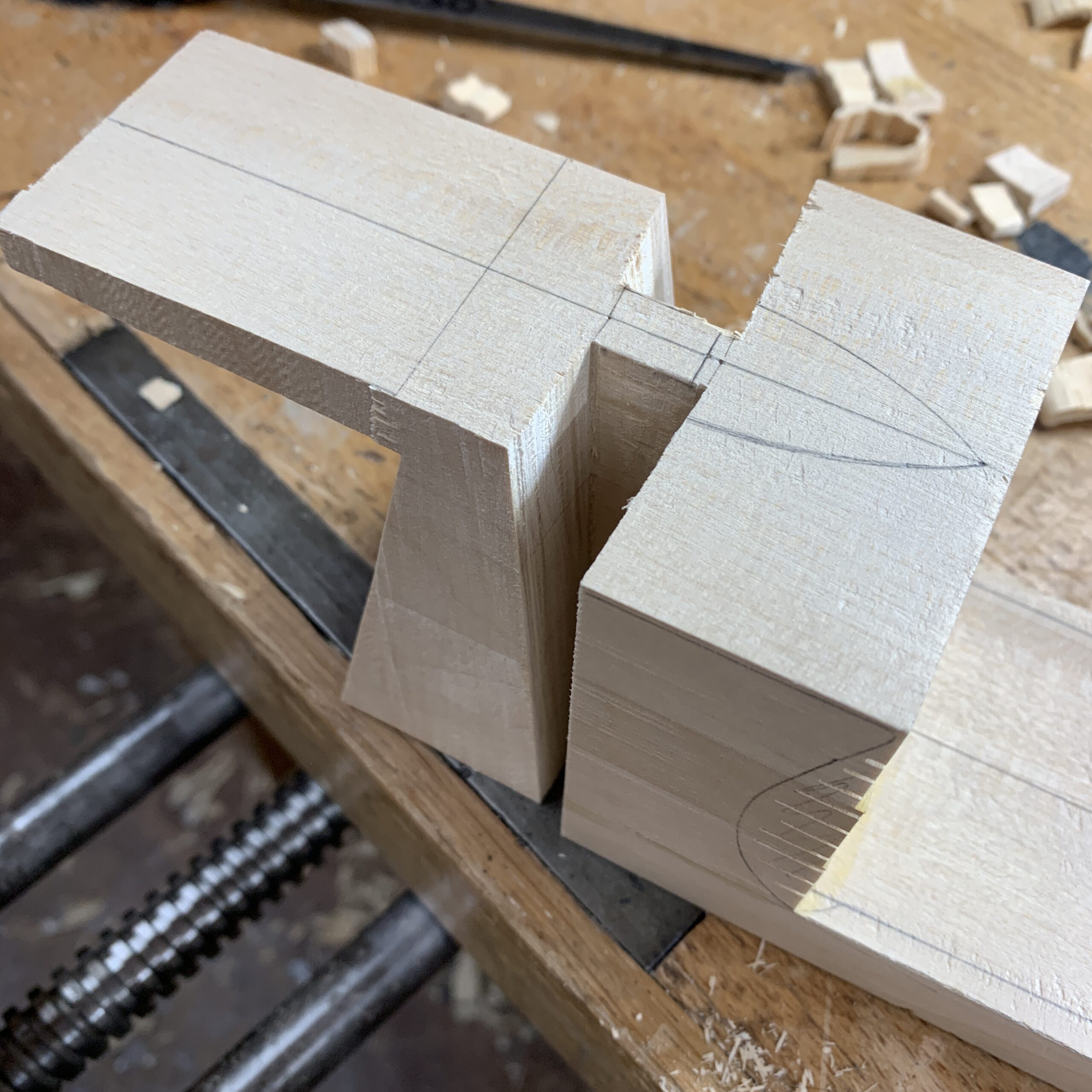

Lime is a traditional wood for carving and was a delight to work with a chisel. It also polishes up well with an interesting, tight grain across the radius of the neck. This piece of Lime is a little more dense (604 kg/m3) than Spanish Cedar, the traditional neck wood for flamenco guitars, but not far off. I routed out the centre and replaced it with a hollow carbon tube for added stiffness and lower weight.

I have worked with Walnut on previous instruments. It makes a very light bridge (13g with bone decoration) and has a nice grain pattern but its relatively low density (630 kg/m3) means that it will suffer from string wear more quickly than traditional Rosewood. To prevent this, I inserted 2mm brass tubing into the string holes.

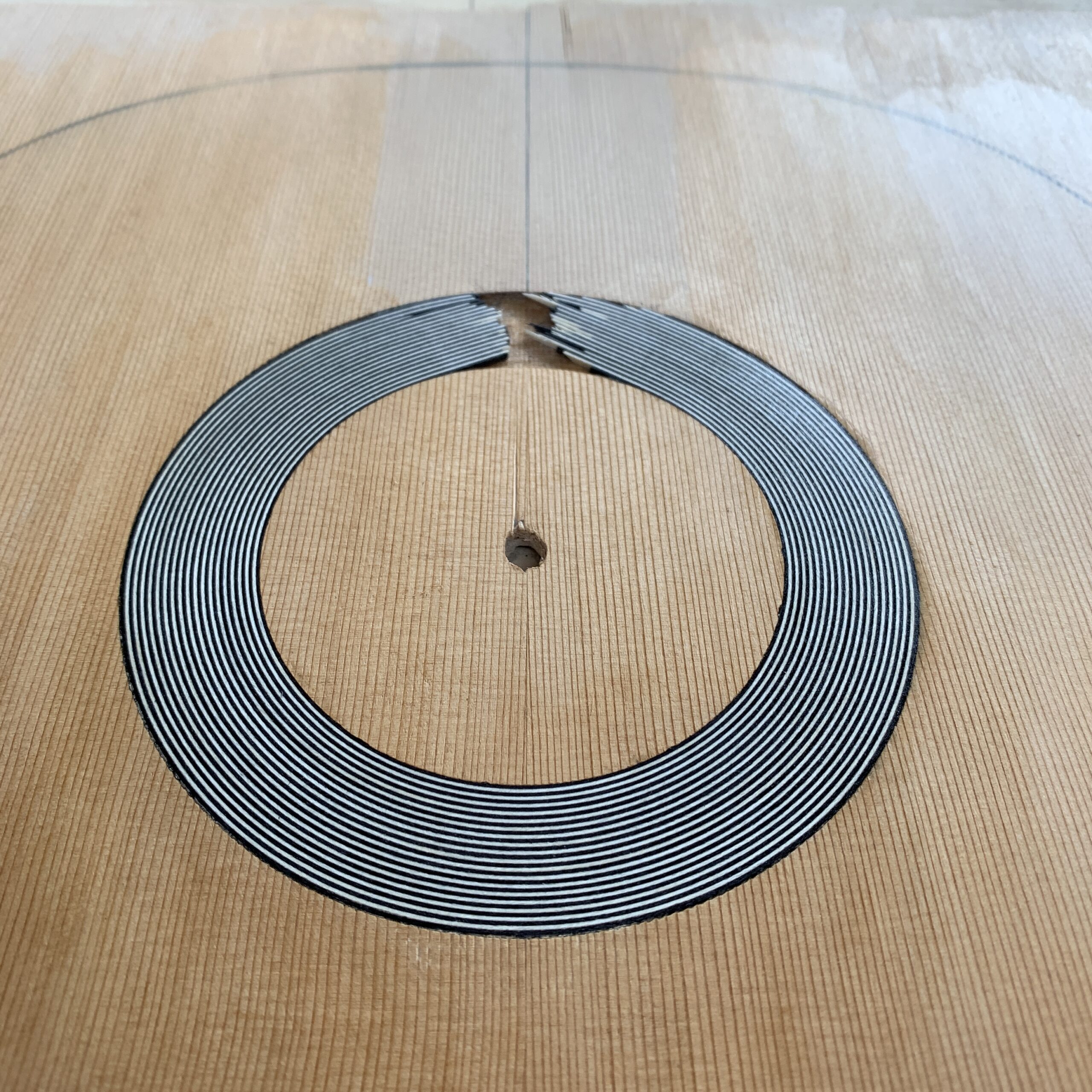

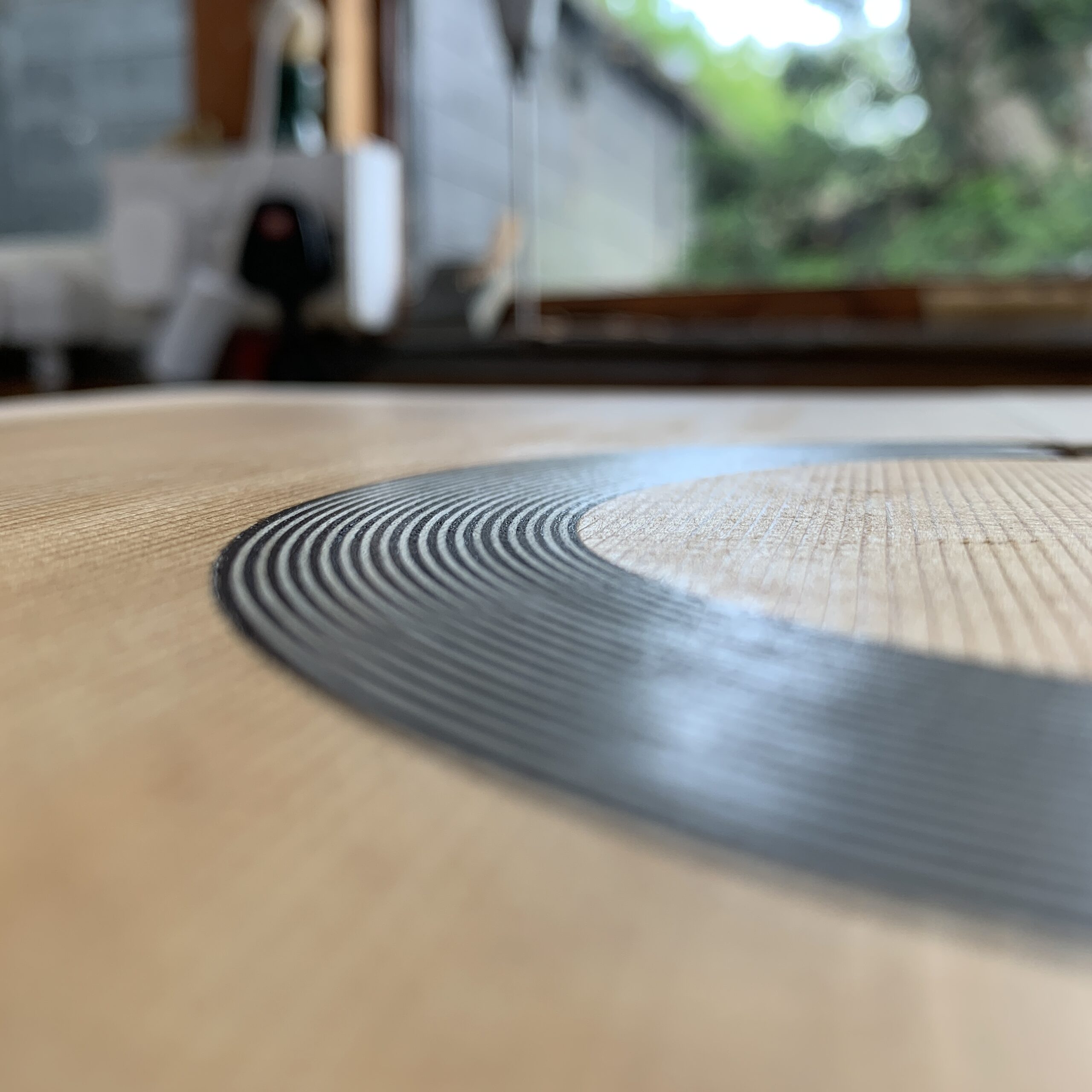

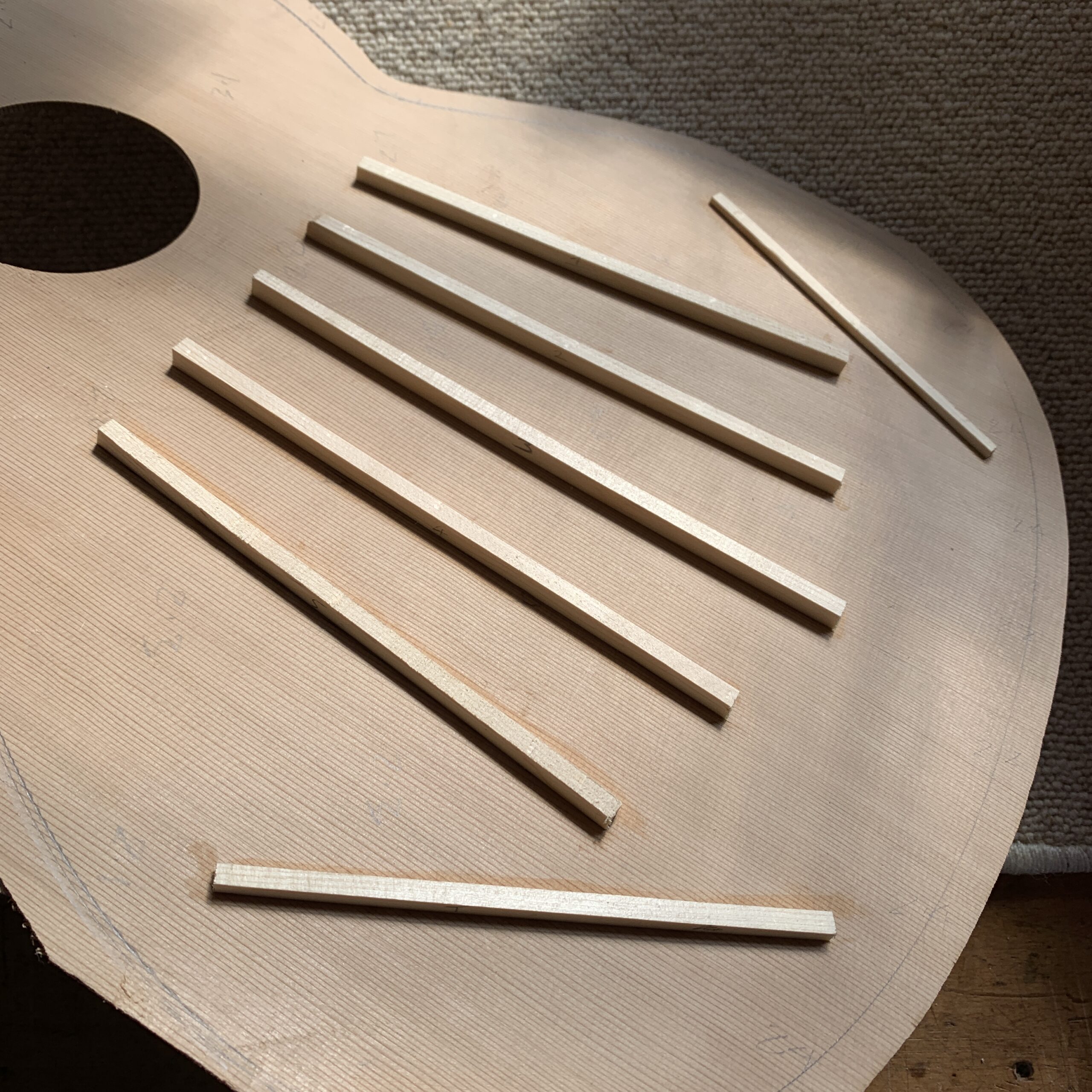

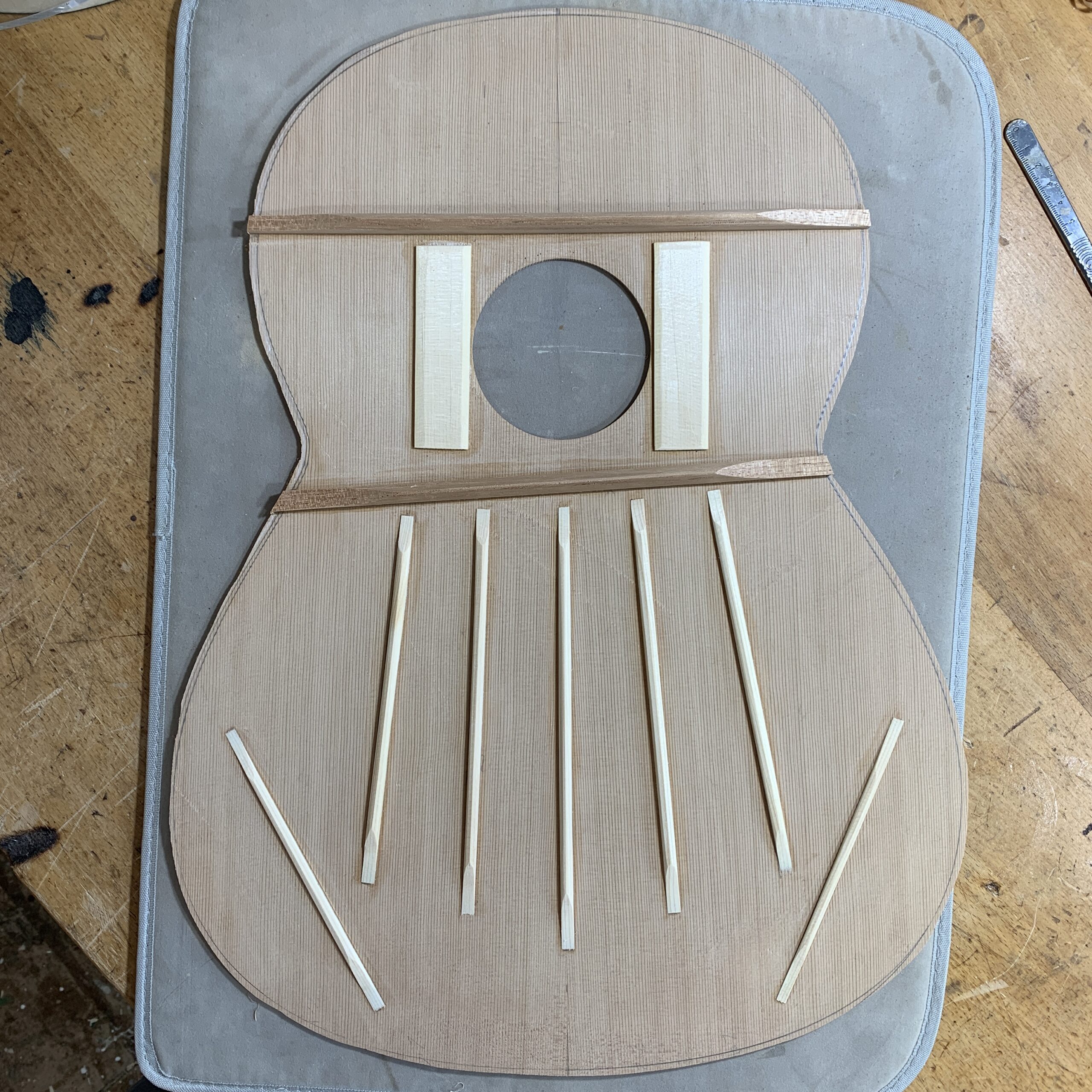

It was the first time I have used Western Red Cedar (WRC) for the soundboard and in many respects it’s a lovely wood for this purpose. It is a very low density wood (347kg/m3) and therefore enables the lightest, most responsive soundboards. It is similar density to the Engelmann Spruce top I used on guitar #2 (385kg/m3) and I will happily use both again in the future. I think the Cedar soundboard gives the instrument a warmer sound than my previous guitars and that it suits classical and jazz more than traditional flamenco, which I have focused on previously.

The Bog Oak fretboard (909 kg/m3) was a nice idea and looks great, but I doubt I’ll use it again. It has quite an open grain and tore easily when planing it. Still, it’s nice to think that you’re working with a piece of wood that is more than 5000 years old.

The overall weight of the instrument is 1288g. Were it not for the metal machine heads, it would weight about 100g less. Once I fitted the tuners, the balance of the guitar shifted noticeably towards the head.

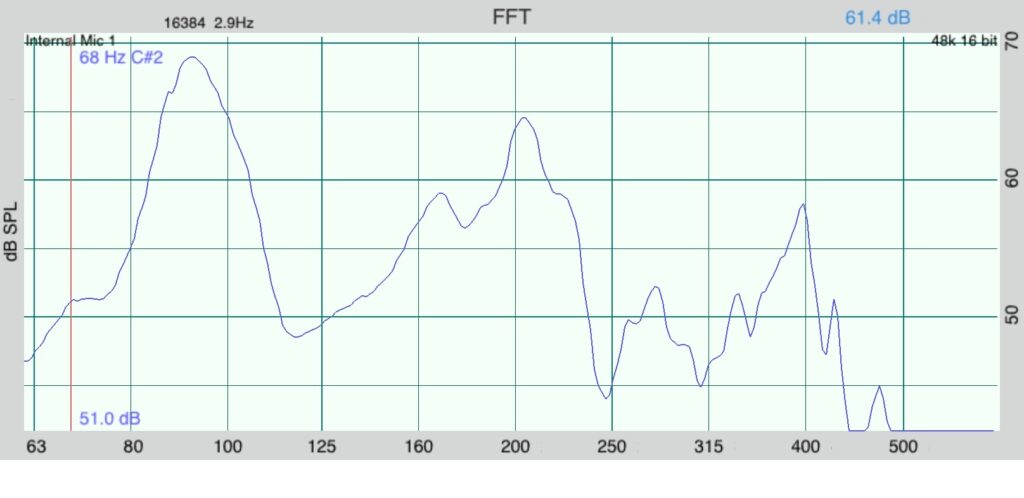

As you can see below, the air resonance of #6 is very similar to #3, as is the weight, once the different tuners are taken into account. However, they do not sound the same, with #3 having a little more volume and a drier, more cutting sound – just what you want from a flamenco blanca. This instrument (#6) sounds different – more versatile – with rounded notes that are even across the fretboard. The different soundboard and neck materials no doubt contribute to this and it is set up with slightly higher action.

- #6: 90Hz (F# -47 cents); 1288g

- #5: 82.8Hz (E +8 cents); 1319g

- #4: 88.8Hz (F +29 cents); 1247g

- #3: 90.8Hz (F# -32 cents); 1189g

- #2: 92.9Hz (F# +7 cents); 1122g

No instrument, whether it is a factory-made model or an individually built hand-made guitar, will sound exactly like another; there are too many variables, not least the individual pieces of wood that are selected which vary within species and from tree to tree.

One way of trying to ensure some consistency is to measure the density and resonant modes of the wood prior to building, following the calculations given by Trevor Gore in his book, Contemporary Acoustic Guitar Design and Build (Vol. 1, section 4.5)1. With these measurements, over time I should be able to establish the physical characteristics of each piece of wood, even within a single species, and then determine the thickness of the top and back plates according to the target frequencies I am aiming for. It will take a number of instruments before I can really start to make meaningful adjustments based on what I’m looking for and should also help me develop my ear, too, by having objective data to refer to when tapping the guitar during the build process and listening to the instruments being played. Neither the traditional intuitive approach (working knowledge), where the luthier taps, listens, holds and flexes, nor the scientific approach (explicit knowledge), which Trevor Gore has explained in his recent book, is exclusive from one-another, and in fact are complementary ways of understanding the relationship between the maker and the materials.

Thank you for posting that. What an amazing work of functional art.