According to Google’s Ngram Viewer, reference to ‘academic labour/labor’ has risen significantly since 1953. Why?

Category: Blog

What we leave behind

My dad, Nigel Winn, died quite suddenly of cancer in 2006 aged 56. Since his death I have been meaning to collect his writing and publish a selection of his poetry. It’s taken me ten years to make time for this, in between having a daughter, getting married, building a house, chasing and holding onto employment and also trying to come to terms with the loss, too.

Dad left behind a collection of poems, a short play and other pieces of writing. He was a bricklayer and carpenter most of his life but started writing actively during the period 1996-2006. During that time, he studied for a BA in English Literature at the University of Lincoln, where he gained a First Class degree. He went on to teach at the university, and was popular among students. Following his death, colleagues established the annual Nigel Winn Memorial Prize for Creative Writing.

His work is quite autobiographical and therefore especially meaningful to those who were close to him. I used Lulu to self-publish this selection of his poetry. It’s very satisfying for me and my family to have a physical copy of his published work and I think that people who knew Nigel may like to purchase a hardback copy of the book, too. I make £0.06p on every copy sold because Lulu won’t allow me to reduce the author’s profit to £0 for some reason. A PDF proof of the book can be downloaded here. Thank you for reading it. He was a really good man.

The Natural Death Centre

As dad was dying I came across a book that helped us in the last weeks of his life and in making the arrangements for his burial. Reading The Natural Death Handbook guided us in what we could do for dad prior to and following his death. It gave us the confidence and basic knowledge of what signs to look for as dad was dying, how to care for his body, and the details of a good undertaker, who allowed us to create the funeral on our terms.

After his last breaths that Spring evening, we removed the catheter and the syringe driver; we washed and laid him out peacefully. Neighbours came to visit him and say goodbye. He remained with us overnight and the undertaker came the next day. We carried him out of the house together, into the back of the undertaker’s car. A few days later, Luke and I helped dig his grave. On the day of the funeral, dad was brought back to the house in the willow coffin he had asked for and mum decorated it with flowers. Members of the family gathered at the house and then we carried his body through the village to the church which was full of his friends.

The vicar said a few words, but left the service largely to us. Afterwards, we took dad outside to the small burial ground, lowered the coffin and shovelled soil over him. Several people remained to fill the hole. It felt right. The least we could do.

~~

Over the years, I’ve thought about the funeral and how the Natural Death Centre and the work they do had such a profound influence at such an important moment in our lives. I’m so grateful for that and pleased to be a supporter of their work.

Here’s a talk by Claire and Rupert Callender, one of the Trustees of the Natural Death Centre.

‘A relationship with the world that provides freedom to actually look at things’

“Most people go to films to get some kind of hit, some kind of overwhelming experience, whether it’s like an amusement park ride or an ideological, informational hit that gives you a critical insight into an issue or an idea. But for those few people who feel they need a reprieve occasionally, who want to cleanse the palate a bit, whether for spiritual or physiological reasons, these films seem to be somewhat effective.

I’ve never felt that my films are very important in terms of the History of Cinema. They offer a little detour from such grand concepts. They appeal primarily to people who enjoy looking at nature, or who enjoy having a moment to study something that’s not fraught with information. The experience of my films is a little like daydreaming. It’s about taking the time to just sit down and look at things, which I don’t think is a very Western preoccupation. A lot of influences on me when I was younger were more Eastern. They suggested a contemplative way of looking – whether at painting, sculpture, architecture, or just a landscape – where the more time you spend actually looking at things, the more they reveal themselves in ways that you don’t expect.

For the most part, people don’t allow themselves the time or the circumstances to get into a relationship with the world that provides freedom to actually look at things. There’s always an overriding design or mission behind their negotiation with life. I think when you have the occasion to step away from agendas – whether it’s through circumstance or out of some kind of emotional necessity – then you’re often struck by the incredible epiphanies of nature. These are often very subtle things, right at the edge of most people’s sensibilities. My films try to record and to offer some of these experiences.”

Source: Peter Hutton: The Filmmaker as Luminist

Peter Hutton’s At Sea was voted #1 of the best 50 avant-garde films made during 2000-2009.

Update 16th July: I have learned that Peter Hutton died on 25th June 2016. I didn’t know him personally but I did correspond with him in 1999 for a screening I organised of two of his films. Of all the work I screened around that time, his was the most influential on me and inspired a lot of the silent footage that went into a film I made a year or so later.

Website for Co-operative Leadership for Higher Education

I mentioned that Mike Neary and I received funding for a new project on ‘Co-operative Leadership for Higher Education’. This is just a note to say that the project has its own website which you can subscribe to:

http://coophe.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk

Recent posts outline the project, relate it to our previous project to develop a framework for co-operative higher education, and look at Edwin Bacon’s work on ‘neo-collegiality‘ and Paul Bernstein’s work on workplace democracy.

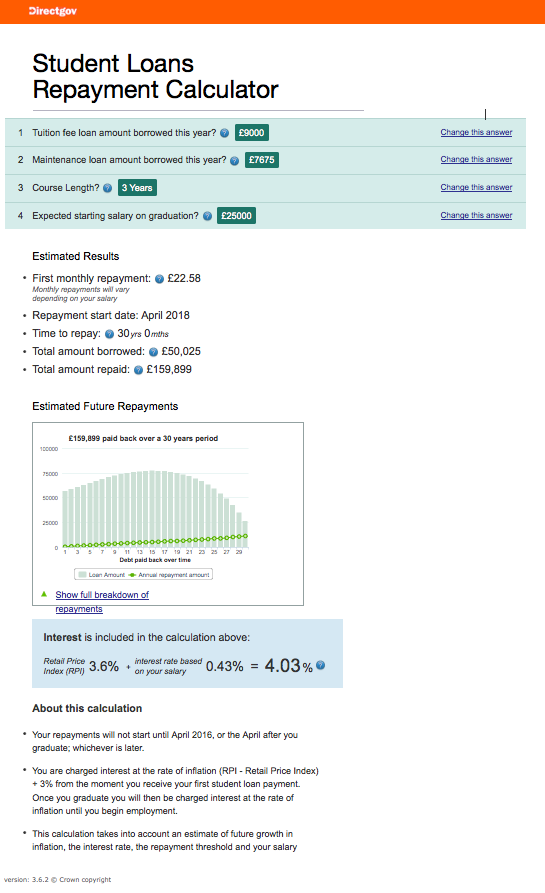

The value of student loans

Andrew McGettigan, has published another useful post on the complexity of student loans. They are complex, not only for the government to model, but also for the borrower to understand how much they will repay and the actual value of the money they repay. The cost of something worth £9000 today is not the same as paying £9000 for it in ten or thirty years time. Andrew makes that clear in an earlier post.

A website like this one, can help us calculate the effect of inflation on the value of money. It tells me that spending £9000 in 1986 would have bought me the same as spending £24,629 today. In 30 years, the value of money has decreased by nearly two-thirds due to 173% inflation. Inflation in the last 30 years has averaged 3.4%, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator. On that basis, £9000 in cash today will be worth (i.e. have the value of) £3300 in 2046.

In late 2013, I was curious about what the actual total amount of money repaid on full student tuition and maintenance loans would be if I were 18yrs old and planning to go to university in London (where I did my undergraduate degree). When I was 18yrs old, I wouldn’t have asked this question, but now with a fixed term mortgage, where I’m told exactly what I’ll pay back (about double what I borrow), and a young daughter who will probably be going to university in a few years, I’ve become more cautious about long-term repayments on large amounts of money.

In 2013, I went onto the Directgov website and used their student repayment calculator and you can see that the total amount repaid is estimated by the government to be shy of £160,000. Note the ‘About this calculation’ section at the bottom:

Again, what the calculator does not do is tell you that the value of money goes down due to inflation, so £160K today is not the same amount of money-value as £160K paid back over 30 years.

I just went onto the Directgov website to use their repayment calculator again, but the website is down, perhaps in response to more good work that Andrew did a few weeks ago on ‘Calculator Caveats‘.

A repayment calculator that is working today is on the Compete University Guide website. Punching in the same numbers indicates that I would pay back £81,286 over 30 years, not £160K. However, under the notes they provide, they say the following:

“The level of inflation is difficult to predict, and will vary over the repayment period. Instead of trying to estimate it, we have taken a different approach:

Inflation will affect the fees, the outstanding loan, the interest due, earnings, and repayments to the same extent.

It is therefore not necessary to calculate the interest charges due to inflation. Instead, all monetary figures, including future earnings, are presented in today’s money.”

As a borrower, I’m none the wiser really. What they seem to be saying is that the £81K figure isn’t really what I’ll be paying back because no-one knows what the value of money (and therefore the value of a wage) will be over a given time. I guess it must be somewhere between £81-160K. It certainly isn’t the £44K that has been discussed in the news recently, stating that English student debt is now the highest in the English-speaking world.

Co-operative higher education conference paper and poster

Mike Neary and I presented a conference paper today at the Co-operative Education conference. You can find it on this page.

We’d really appreciate comments on the framework we have developed in the paper and is illustrated below.

Co-operative Leadership for Higher Education

Mike Neary and I have been awarded funding by the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education to focus on ‘co-operative leadership’ in the higher education context. Below is the introductory section of our research proposal. You can read the rest on Mike’s blog. Here’s a link to the project blog.

The aim of this research is to explore the possibility of establishing co-operative leadership as a viable organisational form of governance and management for Higher Education. Co-operative leadership is already well established in business enterprises in the UK and around the world (Ridley-Duff and Bull 2016), and has recently been adopted as the organising principle by over 800 schools in the United Kingdom (Wilson 2014). The co-operative movement is a global phenomenon with one billion members, supported by national and international organisations working to establish co-operative enterprises and the promotion of cooperative education. The research is financed by the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education’s small development projects fund.

Higher education in the UK is characterised by a mode of governance based on Vice-Chancellors operating as Chief Executives supported by Senior Management teams. Recent research from the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education on Neo-collegiality in the managerial university (Bacon 2014) shows that hierarchical models of governance alienate and de-motivate staff, failing to take advantage of research-based problem solving skills of staff operating at all levels, not accounting for the advantages to organisations when self-managed professionals interact with peers on matters of common purpose, particularly in knowledge-based industries.

The co-operative leadership model for higher education supports the ambition for more active engagement in decision-making to facilitate the best use of academics’ professional capacities, but framed around a more radical model for leadership, governance and management. Members of the co-operative university would not only be involved directly in decision-making and peer-based processes that make best use of their collective skills, but have equal voting rights as well as collective ownership of the assets and liabilities of the co-operative (Cook 2013). This more radical model builds on work done recently as part of a project funded by the Independent Social Research Foundation (ISRF) to establish some general parameters around which a framework for co-operative higher education could be established (Neary and Winn 2015). One of the key issues emerging from this research is the significance of co-operative leadership – the focus of this research project.

How can universities be transformed so that they center on public goods in teaching, research, and community engagement?

Mike Neary and I will be speaking in June as part of a theme on ‘How can universities be transformed…’ at the UNIKE conference in Copenhagen. We will be discussing our recent research project on co-operative higher education and contributing to the overall discussion on the public and community purposes of universities. Below is the overall conference strand description.

Within higher education, values such as democracy, solidarity, public good and community benefit are increasingly overshadowed by systems of management based on Taylorism and hierarchical control. The session explores these trends and draws on participants’ practical experiences, lessons learnt, and best practices to suggest alternative organizational forms. The session aims to use these experiences to promote both discussion and first steps in developing an audit tool to use to evaluate universities and hold them accountable for their promotion of public goods. Finally, participants will identify some alternative pathways to address the decline of public goods in universities: reform of existing institutions, creation of new institutions, etc.

The group will organise a workshop in which participants will brainstorm the principles, issues, approaches (democracy, social justice, pedagogy, ownership, financing, governance) in groups to address the identified problems, moving forward.

Conference programme (PDF)

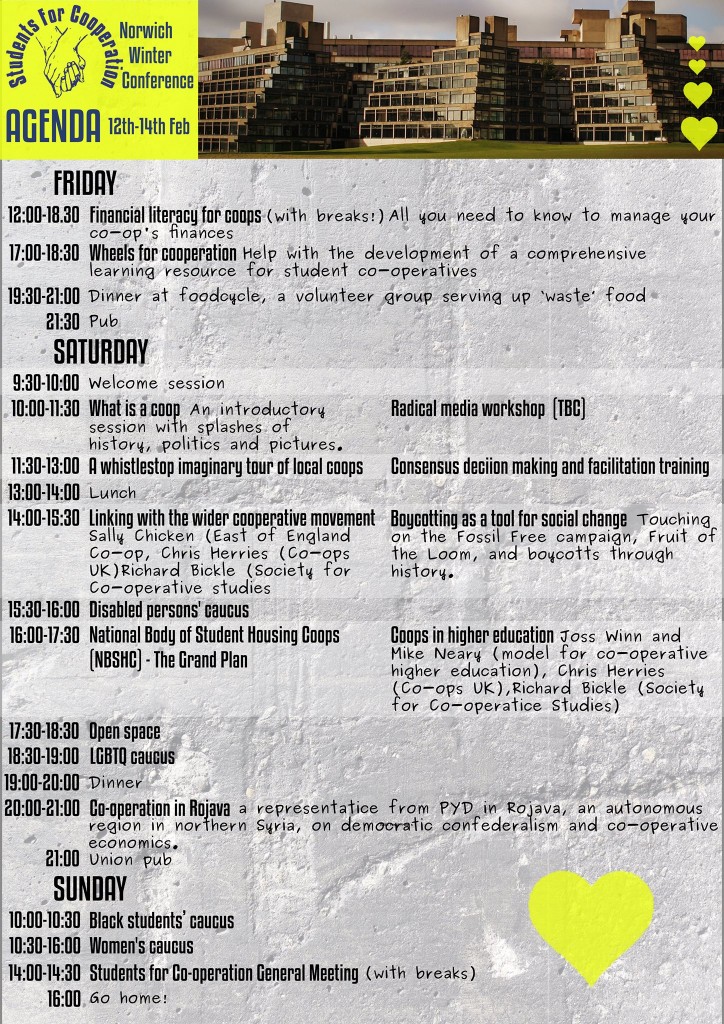

Students for Co-operation Winter Conference

Students are increasingly organising themselves around co-operative values and principles, providing goods, services and housing to their members. There are a growing number of student housing co-ops (in Sheffield, Birmingham, Edinburgh…), an emerging national body of student housing co-operatives, a national federation of student co-ops, and a new network of young co-operators led by AltGen, an organisation that supports young people to set up their own worker co-operatives.

Highlights from Young Co-operators Weekend in Bradford from Blake House on Vimeo.

Students for Co-operation are holding their national winter conference at the University of East Anglia, February 12-14th, and I will be attending again to jointly run a workshop on co-operative higher education. Mike Neary and I attended a national meeting last June to run a workshop on co-operative higher education at the start of our ISRF-funded research project. Now approaching the end of the project and having run five more workshops on different themes relating to co-operative higher education since then, it will be good to return and discuss some of our findings.

Update on ‘Beyond public and private’ research project

With the exception of a few thoughts on an unexpected and emotional encounter, I have not had much to add to this blog since completing my PhD. However, as always, work continues and is being reported on the Social Science Centre website, where Mike Neary and I post about the progress of our ISRF-funded research project: ‘Beyond Public and Private: A Model for Co-operative Higher Education‘.

You’ll see from the updates on the SSC website that we are over half way into the project, having completed three of the five planned workshops and focus groups: Pedagogy, Governance, and Legal frameworks. We are also interviewing individuals regularly and almost 80 people (students, academics, ‘co-operators’, and others) have joined our project mailing list, which clearly has the potential to become a formal research network into co-operative forms of higher education. We are meeting many really interesting and experienced educators, researchers and activists through this project, which, as we reported from the first workshop, is developing around three inter-related concerns for co-operative higher education:

1. The Social historical movement: A co-operative form of higher learning conscious of its connection to and engagement with the historical and logical development of the co-operative movement.

2. The Organisation: The institutional form of the co-operative will substantiate the political, moral and ethical values of the co-operative movement, set within an educational context.

3. The Praxis: The pedagogy will be grounded in the practices and principles of co-operative learning, recognising that much can be learned about how to be a co-operator-student/teacher (i.e. ‘scholar’), while at the same time acknowledging that co-operative practices are already endemic in radical social interactions.

Each of the workshop themes can be ‘mapped’ on to one or more of these three higher level components of the ‘model’.

I am also thinking of how other concepts might express or expand on the five themes. For example:

Pedagogy = Knowledge

Governance = Democracy

Legal = Bureaucracy

Business Models = Livelihood*

Trans-national = Solidarity

*This is a word that came out of a discussion on how we want to move away from the use of some conventional terms, such as ‘business model’, that do not adequately capture the essence of our concerns. In a world where business and work is continually in crisis, a ‘business model’ seems increasingly anachronistic to what is fundamentally required.

Our project aims to develop a ‘model’ for co-operative higher education, or perhaps a ‘framework’ is a better word to use. Nevertheless, models and frameworks are forms of useful abstractions and at this stage of our work, sketching out relational themes, concepts and approaches is a necessary and useful exercise. This has been evident in the way that the categorisation of ‘routes’ to co-operative higher education that I outlined in my earlier paper have been a useful reference during each of the workshops:

Conversion: How to convert an existing university into a co-operative, either through a planned ‘executive’ decision or out of necessity, as in a worker takeover of a failing institution. In the UK, this route would seek to maintain any remaining public sources of funding and the ‘university’ title.

Dissolution: How to create a co-operative university from the ‘inside out’, through the gradual increase of co-operative practices, such as co-operatively run research groups and departments; programmes of study in aspects of co-operation, social history, political economy, etc.; the conversion of student halls into housing co-ops; changes to procurement practices that favour co-operatives, and so on. Through this route, the university might eventually become a ‘co-op of co-ops’.

Creation: How to create a new co-operative form of higher education. This tends to be where our workshop discussions end up. It is the least compromising of each of the routes and in some ways the most ambitious. Discussions of this route are intensely practical in their focus and unashamedly utopian, too. This route draws inspiration from the huge numbers of actually existing worker and social solidarity co-ops around the world.

So, in summary what might we have with all of this?

Three routes to co-operative higher education: Conversion, dissolution, creation

Three concerns for the overall project (regardless of route): The social historical movement, the organisation, the praxis.

Five themes for practical and theoretical work (an anti-curricula or course of action): Knowledge, democracy, bureaucracy, livelihood, solidarity.

Mike Neary and I will shortly be writing up an interim report on the project at the request of the LATISS open access journal and will attempt to summarise all of this for the benefit of our own thinking and that of all the research participants.

If you would like to contribute in some way to the project, we have two more workshops (Nov 20th, Jan 29th), each followed by an online focus group, and we’d be happy to interview you too. We will also be issuing a survey in February which will be a last ditch attempt to gather data before we analyse it and write it up in the Spring.