Mike’s published work can be found via the University of Lincoln research repository. Work published prior to his time at Lincoln (pre-2007) is not complete on that list. More can be found on Google Scholar, but the list includes the work of other people by the same name. Mike also wrote on his blog between 2014 and 2017. If you have trouble locating an article or chapter, please contact me. I may have it.

In December 2024, a book of Mike’s work was published by Peter Lang.

~~~

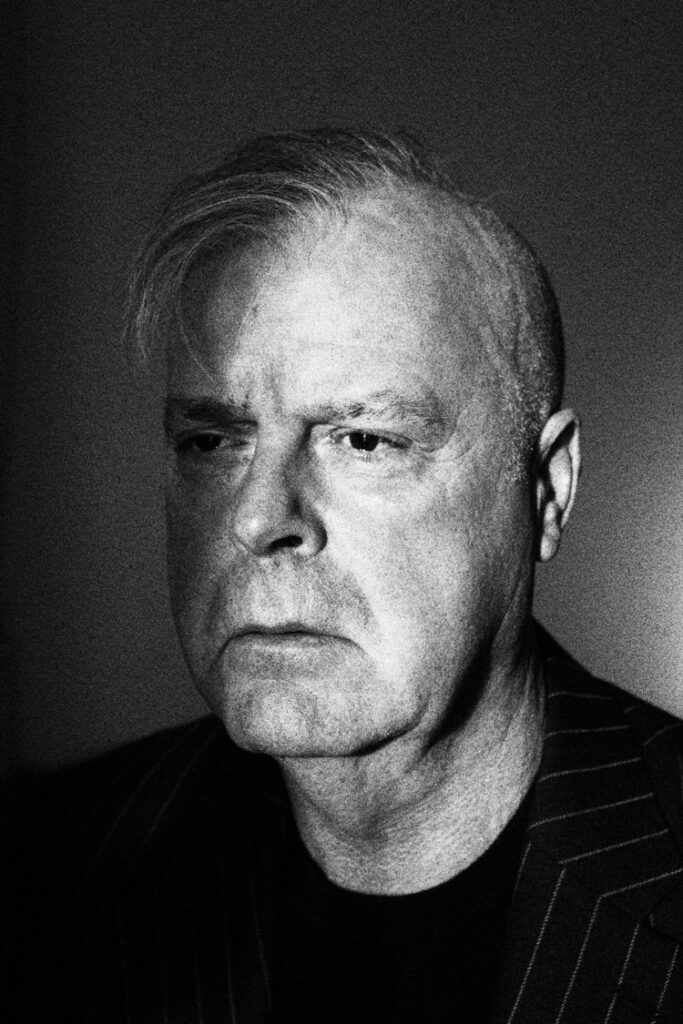

Professor Mike Neary

Mike Neary joined the University of Lincoln from Warwick to become Dean of Teaching and Learning, and Director of the Centre for Educational Research and Development in 2007. During his 15 years at Lincoln, Mike also served as Director of the Graduate School, Professor of Sociology and Emeritus Professor of Sociology. He was a National Teaching Fellow and Principal Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and awarded honorary lifetime membership of Lincoln Students’ Union in 2014.

During his time as Dean of Teaching and Learning, he led two ambitious and openly subversive projects: Learning Landscapes, which demonstrated why academics should have a greater role in the design and governance of university estate, and Student as Producer, an institutional strategy to make research-engaged teaching the default for all teaching and learning at Lincoln. Although labelled a ‘teaching and learning’ project, the organising principle of Student as Producer, like Learning Landscapes, was the democratisation of higher education, aligning students and academics towards the shared production of knowledge.

Both projects were deemed successful at Lincoln and have been influential across the UK and internationally. However, Mike understood and accepted that Student as Producer would be reinterpreted and recuperated as various forms of ‘student engagement’. His critical response to this was to establish, with others, the Social Science Centre, Lincoln, an independent co-operative for higher education that was democratically owned and run by its members. It was through the Social Science Centre, that its members developed further the theory and practice of Student as Producer. With Mike, they drew on the radical history of the worker co-operative movement, asserting that the means of knowledge production (i.e., the university) should be democratically owned and controlled by its scholars, both teachers and students. This work inspired the Co-operative College, Manchester, and other educational co-operatives around the UK, to pursue the creation of a federated co-operative university. At the time of his retirement, Mike became Chair of the Co-operative University’s interim Academic Board at the Co-operative College. A formal submission for a federated co-operative university was made to the Office for Students, but plans were thwarted by the pandemic. Throughout this whole period, Mike tried to encourage everyone – students, activists, local citizens – to find their voices in the various spaces and projects because, despite his professorial stature, he knew that we all have a lot to learn from each other.

Mike published extensively on higher education policy, critical pedagogy and academic labour. His written work is characterised by both serious social critique and daring intellectual creativity, evident in his last book, Student as Producer: How Do Revolutionary Teachers Teach? The book consolidated over a decade of intensive theorising and extensive practice aimed at defending and revitalising the role of the university as a community of teachers and students drawn together around the production of knowledge for humanity. Connections can be found in this work with earlier co-authored books, on labour theory and the critique of money. He also undertook research on the labour movement in Korea, and the prospects of regeneration in coalfield communities. His PhD was a critical history of youth training – he was a youth worker before entering academia.

Mike’s intellectual influences were diverse: he greatly admired the Canadian scholar, Moishe Postone’s interpretation of Marx and saw himself working in the tradition of critical political economy and ‘value-form theory’. His PhD supervisor at Warwick, Simon Clarke, always remained a model of intellectual rigour and clarity. Alongside these eminent Marxist scholars, Mike drew inspiration from avant-garde art; examples such as Brecht, Burgess, Epstein, Klee, Dada and Vorticism are woven into his writing. In one article, he brought together the work of Karl Marx and the Medieval Bishop of Lincoln Cathedral, Robert Grossteste, in another he united Marx’s theory of value with Einstein’s special theory of relativity. He was always restlessly trying to bring the natural and social sciences together into ‘one science’.

Mike was a much-loved and greatly respected colleague, known for his warm, welcoming approach and great sense of humour. He is remembered as being inspirational to many, colleagues and students alike. He made a profound and lasting contribution to the University of Lincoln, and other institutions in the UK and internationally, as a committed revolutionary, a genuinely bold and innovative thinker, intent on reinventing the core purpose of higher education.

Kate Strudwick, Dean of Teaching and Learning and Joss Winn, Senior Lecturer, University of Lincoln.

~~~

Eulogy for Mike, 14th February 2023 – Joss Winn

Mike was my friend, colleague, PhD supervisor, and co-author of ten articles and book chapters. Because we worked closely together for over a decade, I thought I would say something about Mike’s creativity; about Mike as an artist and how the influence of other artists can be found in his writing. Mike’s understanding of humanity was that we all have a natural capacity for creativity which has been suppressed. I believe that learning from and teaching Mike’s work can help us recover that creativity.

Many of you know Mike as a social theorist. Working with Mike, it became clear to me that creating theory is a type of artistic practice: exploratory, expressive, speculative, risky, and challenging, but ultimately productive because creating social theory changes the way we see the world, just like other forms of art, such as painting, theatre, sculpture or architecture.

Throughout the time I’ve known Mike, he would draw on the work of other artists to help develop what he was trying to say: for example, the writing of Bertolt Brecht and Anthony Burgess; Jacob Epstein’s sculpture, Rock Drill; Paul Klee’s painting, Angelus Novus, and the avant-garde art movements of Dada and Vorticism. You will find in Mike’s writing, a highly original attempt to bring together the work of Karl Marx and the Medieval Bishop of Lincoln Cathedral, Robert Grossteste. There is also a wonderful piece of writing called ‘Pedagogy in Paradise’, where he experiments with rythmnanalysis and photography during his time in Chile. A favourite example of Mike the artist is the writing he produced with Glenn Rikowski, that unites Marx’s theory of value with Einstein’s special theory of relativity. When I first read that article, it overwhelmed me, like great art does. I was in awe of what they had set out to do.

I don’t know if Glenn’s experience of writing with Mike was similar to mine, but I will finish by telling you about how Mike and I would write together. At regular intervals in the writing process, it would involve us sitting together and reading our work out loud to one another, a bit like actors reading a script around a table before they rehearse on stage. By taking it in turns to read something out loud we’d have to speak slowly for the other to take it in, knowing the tone and texture of our respective contributions had to work together, to become a unified whole – one voice, not two.

I miss those meetings but thankfully, I still hear his voice when I read the words.

~~~

We Stammer

Spoken by Mike Neary. Recorded by Nik Farrell Fox, January 2017.

~~~

A Personal Paean to Mike Neary – Nik Farrell Fox, 29th March 2023

Mike and I were thrust together by happenstance in a dialectical dance of necessity, fortune and chance. My new next-door neighbour would soon become the best friend I’ve ever had and the finest, most exemplary man I’ve ever known. Tall, handsome and graceful, his eccentricity was magnetic, his intellect was profound and his face exuded the gentleness and warmth that endeared him to so many. His lilting voice was soft and welcoming but not without authority and some piquancy when irked or when expressing outrage at the world’s immorality and grotesque injustices. The ‘pedagogy of hate’ that he espoused as a theoretical tool for destroying capitalism on the surface sat contradictorily within a man so gentle and kind. But, as with many kissed by the revolutionary spirit of freedom, Mike’s ‘hatred’ was of a pure, redemptive nature fuelled by a deep love for his fellow human beings and a great distress at their enslavement and enforced predicaments.

Although we did many things together, the details of which I’ll remember with ultimate fondness, it was our revelatory and blissful walks around the West Common that I miss most of all. We would walk around the perimeter, with each stage host to a different topic. From the gate to the northerly tip we discussed football – results, managers, players, favourite and least favourite pundits, past exploits on the pitch when we were youngsters captaining our respective school teams, funny anecdotes and leftfield observations pertaining to the most tenuous of connections. I always found Mike very humorous, interesting and playful in his observations. From here we would then traverse the next section with academia taking over, discussing where we were at with our research. Mike listened to my protracted ramblings with an encouraging, comradely ear while showing the greatest modesty in relation to his own, far more portentous deeds, which impressed me nonetheless. For the next mile or two we assailed each other with the jargon of philosophical discourse – I hit him in the jowls with Sartre, Foucault and Nietzsche while he floored me with Marx, Negri and Ranciere. Despite the intensity of our reasonings, protestations and proclamations, never for a single second did our words ever become barbed or our moods hostile. I loved arguing and finding agreement with Mike for he was an intellectual giant and a very sporting gladiator. After all, our disagreements were slight, for our minds thought similar things and our revolutionary hearts beat in tempo. For the final part of the walk, once our academic muscles had been sufficiently exercised, family became our topic of conversation in which Mike would always take a genuine interest in the minutiae of what I told him about my Loved Ones before he told me with great affection about his. Back at the Common gate, we would on occasion just want to keep talking and would repeat the circuit, trampling over the same topics and clods of earth. Otherwise, we just shuffled back together like two contented creatures along West Parade before disappearing back into adjacent houses until the delight of doing it all again in a week’s time.

Nietzsche (not him again, Mike groans), saw friendship as life’s most precious gift and as a bona fide recipe for a healthy society. There were, he said, three essential components to any great friendship – agonism (where, through sublimated competition, we each grow and develop), the sharing of joyful experiences (in which we partake of common perceptions and actions), and the virtue of bestowing (in which we pass on our knowledge and attributes as ‘gifts’ to the other). All three were ever-present in my unwavering and unbesmirched friendship with Mike, but as, Nietzsche stated, it is the bestowing virtue of friendship that carries the greatest weight. Mike’s life was a gift to us all who knew and loved him, and the knowledge, kindness and good vibrations that he bestowed will live on as vibrant memories in the hearts of many others like my own. To echo the final words of his final book, he taught us (in a soft Geordie accent) how to learn from each other and flourish together as ‘a pedagogy of excess in a world of abundance’

Adieux, my precious friend, a human being, as Nietzsche spoke prophetically of the Übermensch, ‘with Caesar’s strength and Christ’s soul’

~~~

Remembering Mike Neary: ‘Teaching as a Collaborative, Political Activity’ – Richard Lance Keeble, Professor of Journalism

Mike Neary had an enormous impact on the University of Lincoln. For Mike (inspired as he was by Marx), pedagogy was always political – and he was not afraid to put his ideas into practice. In the end, his ideas about the Student as a Producer and Learning Landscapes transformed teaching practices across the institution. But for Mike the political was also the personal and so he devoted a lot of his energy to supporting colleagues and students at an individual level.

I personally benefited from this support in many ways. One of his ambitions was to inject the research-led post-graduate culture wherever possible into the undergraduate culture. Responding to that initiative, my late friend and colleague John Tulloch, Head of Journalism, and I launched the country’s first BA in Investigative Journalism (with a prize of £200 for the best student of the year – donated by the celebrated reporter John Pilger). For this degree, the students had no formal class teaching in their final semester: instead, they were able to dedicate the whole of their time to researching and writing their individual investigative projects. They would meet as a group from time to time to discuss progress – and any particular practical or ethical issues. But essentially I met them on a personal basis as if they were post-graduate research students. I had been teaching journalism since 1984 – but the work produced by the students on this programme was amongst the best I had ever supervised. And Mike was thrilled to hear about the success of the degree.

Mike arrived from Warwick University as a recipient of a National Teaching Fellowship. When I applied in 2011, he was thus able to give me crucial advice on how to present the 5,000-word submission document. When he saw my original draft he said simply: ‘Fine – but just add a bit of theory.’ Which I did – and when I won the fellowship Mike accompanied me to London for the award ceremony.

For a few years I joined Mike, Joss Winn and others in setting up the Social Science Centre in Lincoln. Mike was clearly angry at the commercialisation of higher education and the immoral, excessive fees charged students. The creation of the Social Science Centre was one of his responses. And its aims sum up Mike’s principles perfectly: ‘SSC believes that higher learning oriented towards intellectual values of critical thinking, experimentation, sharing, peer review, co-operation, collaboration, openness, debate and constructive disagreement point towards a better future for us all. The centre works to create alternative spaces of higher education whose purpose, societal value and existence do not depend on the decisions of the powerful.’

A number of speakers at the moving ‘Stammering as Dada’ commemorative event mentioned Mike’s passion for football. I (a Notts and Forest supporter being a Nottingham lad) also liked to indulge in footie gossip with him (and after I retired in 2013 we would meet up from time to time). One thing I particularly remember him saying was: ‘Actually when I go to a game I’m more interested in watching the ways in which the managers react than the actual football.’

Mike, always acutely aware that teaching is at its core (its heart) a collaborative, highly political activity, was an inspiration for me – and for countless others.

~~~

Tribute to Mike – Alan Gurbutt

Life feels short now that Mike has gone. He was a gentle person and kind. He showed me kindness, despite my awkwardness towards inequalities in state education. That was my problem and he couldn’t fix it. Mike probably didn’t realise that his teachings evoked answers within me on how Capitalism impacted my family life growing up in a council house in the 1970s, a rare privilege today, and the issues we faced not having enough money. I learnt about socioeconomic trauma through his teachings and this gave me some closure. I remember Mike being at meetings of the Social Science Centre. He was always welcoming with a smile. The last time I spoke with Mike was at the University of Lincoln. He wished me well with my nurse training and expressed how pleased he was that I was reading mental health. Mike also encouraged my daughter’s passion for learning. I wish he could have been here longer. I loved and admired him.

~~~

Plenary of the British Conference of Undergraduate Research and World Congress of Undergraduate Research at Warwick – Written by colleagues from the international Undergraduate Research community.

Our story of Mike Neary starts somewhere back in the early years of this Millennium when Mike was a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Warwick. Mike brought together a team of colleagues from many disciplines and many places to create the Reinvention Centre for Undergraduate Research, one of around 80 centres of excellence in teaching and learning funded at that time. Parts of the story that unfolds here are recorded more formally in the University of Warwick’s recent submission to the Teaching Excellence Framework.

Like many of us, Mike was sold on the benefits to our students’ education of undergraduate research and he was always enthusiastic about it. But Mike had the vision to see that promoting undergraduate research could have, and indeed has had, a transformative effect on universities and on us. Mike could always think beyond. He instilled his passion for Undergraduate Research in all of us and that’s embodied in everything we do. He always asked what students might have to offer and what their role might be.

In 2007 the Reinvention Centre hosted a conference called ‘The Student as Producer’, one of the first times this concept was presented in public. As well as the extensive academic debate, we discussed how to actually get on and change things in our universities. Mike had some spare funding and needed to spend it quickly. He bought a minibus! This was a typically surprising but brilliant move. The minibus had Reinvention blazoned down its sides and was a symbol of how we could connect our students to the worlds beyond the university campus.

The minibus took conference delegates to the innovative Reinvention Centre at Westwood, the first time most of us had seen beanbags in a university classroom! Mike understood the need to reinvent the spaces we study in to literally transform the landscape of higher education. The Oculus here at Warwick is a physical embodiment of Mike’s legacy, with many design features from the experimental classroom, which has now sadly gone. Around the country we see new university buildings that are directly inspired by Mike’s ideas – typically having lots of amazing classrooms for students and a few rather miserable offices for academics!

Also in 2007, Mike moved from Warwick to the University of Lincoln where he took up a senior leadership role. One of his major achievements was to persuade the University of Lincoln to make ‘Student as Producer’ its signature pedagogy, and it featured in its strategies, website, and student prospectuses. Getting buy-in from the Vice-Chancellor and the senior management team to a concept that Mike openly said had its roots in Marxist philosophy, is nothing short of amazing.

At Lincoln Mike engaged with colleagues and of course with students in his characteristic way. Mike brought people on and he helped them learn the craft of navigating higher education. Despite being a senior leader, or he would have said because he was a senior leader, Mike often immersed himself in student life, being seen quietly sitting in the corner at a student Marxist society event or on the back seat of a minibus heading to London with students protesting tuition fee increases. Mike was the ultimate critic of university bureaucracy but could use it well to achieve his goals. Always principled, Mike never lost sight of what he was trying to achieve. In retirement, Mike planned to develop his ideas around cooperative universities, work that others will now have to finish.

Mike was an insider outsider. He had what Jonathan Rée calls the courage of his anachronisms. He railed against the technocratic university and invited us to continually challenge the dominant discourse. He encouraged students to move beyond capitalist realism and to understand that they can change things. We really need Mike’s voices to continue being heard. Mike was not ideological. He saw universities as part of the destructive neoliberal project and drew on Paolo Freire’s call to constantly seek change and to reinvent. Mike embodied critical hope. He could see darkness in the world and that, while there is not necessarily light at the end of the tunnel, if we restlessly reinvent we can dare to hope.

Mike was very political and knew that education is a deeply political project building us as individuals and collectives to make the world a better place – he had democratising zeal. He saw possibilities even in elite institutions for education and research to mutually reinforce each other in transformative ways. He was brave and urged us not to be scared to talk about values in designing our universities. He never shied away from awkward situations yet despite the challenges he saw, he was never combative. Instead he was thoughtful and kind, though always with an edge.

Beyond the UK, Mike’s ideas and scholarly writing were seminal in establishing the underlying framework and ethos of the Australasian Council for Undergraduate Research, which is, to this day, a vibrant community of academics and students working together to promote and advance undergraduate research in Australasia. Mike remained a member of the ACUR Steering Committee until his untimely death.

Mike believed in the potential of others and provided them with opportunities and encouragement. He was generous, humane, principled, restlessly creative and fearless in pushing against the boundaries in education. He gave so many of us fantastic starts or changes of direction in our careers at Lincoln and at Warwick. Mike would do anything for you and he changed our lives. His impact is immeasurable. He truly was an inspirational figure and the kindest of friends.

Mike loved the British Conference of Undergraduate Research. He would have been so proud to see the hundreds of students from around the world presenting their work here at Warwick. Mike Neary should be here today.

~~~

Tributes by Richard Hall and Ana Dinerstein in Network, the magazine of the British Sociological Association.

~~~