This chapter discusses the peculiar nature of the ‘commodity’. I start by chopping the word down to its etymological roots and then reanimate it as the ‘commodity form’. In order to explain a single word, I have to introduce others: labor-power, abstract labor, socially necessary labor time and value. I then discuss the commodity of education, students as consumers and as producers. Finally, I conclude that the university (or college, or school) is a fetish that conceals the pervasive social power of the commodity-form.

Winn, Joss (2021). Commodity. In: Themelis, Spyros (Ed.), Critical Reflections on the Language of Neoliberalism in Education: Dangerous Words and Discourses of Possibility. London: Routledge.

Tag: value

Review: Negotiating Neoliberalism. Developing Alternative Educational Visions

Below is an extended pre-print of a book review for Power and Education journal. The first half talks directly about the book; the remainder tries to offer a critical response.

Rudd, Tim and Goodson, Ivor F. (Eds.) (2017) Negotiating Neoliberalism. Developing Alternative Educational Visions. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

This book, comprised of 13 peer-reviewed chapters, presents a coherent understanding of neoliberalism as an ideological project, the ways in which it is made manifest in all areas of formal education, and the need to develop conceptual and practical alternatives that serve humanity rather than the economy. The focus of the book is equally weighted between discussions of compulsory and higher education and similarly balanced between theoretical and empirical scholarship and research. In addition to the thematic coherence of the chapters, most of the authors engage with Goodson’s framework of ‘The five R’s of educational research’ (2015): Remembering, regression, reconceptualization, refraction, and renewal. In their introduction to the book, editors, Rudd and Goodson, extend this to ‘six R’s’ with the addition of resistance.

This framework serves the book’s authors well. For example, Mike Hayler argues that formative assessment can be combined with the principles of critical pedagogy to resist data-driven target-setting and similarly, Peter Humphreys proposes a more personalised education that is “invitational” and wholly democratic. Ingunn Elisabeth Stray and Helen Eikeland Voreland employ refraction to study UNESCO’s Education For All project through the cases of Norway and Nepal and conclude that the project is in danger of becoming “an exercise of political violence” that needs to become more sensitive to national and cultural contexts.

Two chapters in the book combine remembering with renewal through the theme of co-operative education. Following a brief history of co-operative education in the context of neoliberalism, Tom Woodin’s chapter discusses an in-school co-operative of more than 80 students who provide peer-support to other students in a variety of subjects. The experience of setting up and running the co-operative has introduced a sense of solidarity and collective purpose among its members. This small example of constituting social relationships differently within a neoliberal context is in itself an education in the possibility of alternatives that can be expanded both within and outside the education system. Co-operatives, argues Woodin, offer a form of “structural innovation” that is capable of proliferating and maintaining a sense of social struggle. John Schostak’s chapter extends this argument by acknowledging the recent movement of co-operative schools in the UK but recognising that without radical changes at the level of the curriculum, there is the “ever present danger of simply reproducing” the status quo. Schostak persuasively argues that the practice of co-operation is itself a form of collective education out of which a curriculum of learning emerges, based on the practice of democracy. The institutional forms that arise from the practice of democracy, solidarity and equality are themselves the subject of study as much as they are the object of collective management.

Richard Hall focuses on academic labour within UK higher education, discussing the influence of ‘human capital theory’ on the way in which the labour of academics is being valorised. What makes the chapter interesting is the way in which he provides a close reading of Marx through which he exposes human capital theory as a theory of productivity that is made manifest in the intensification of labour time. This now operates in policy and in practice inside higher education and elsewhere. Hall’s response is to work against this reconceptualization of academic labour by advocating solidarity inside and outside universities so that academic labour, including that of students, is recognised as having the same fundamental characteristics as other forms of labour and is therefore subject to the same crises of capitalism that are the focus of other social movements. Hall is not arguing for the militant defence of academic labour, but to see it for what it is: wage labour subject to the alienation of the capitalist valorisation process, and as such should be abolished. Resistance to the processes of work intensification are all the while necessary, but the discovery of new forms of social solidarity and large scale transformation (rather than reformation) of political economy are the end goals.

A chapter which shares a key critical category with Richard Hall’s is that of Yvonne Downs, who focuses on the difficult concept of ‘value’. She argues that “little is known about the value of higher education at all” (59) and offers critiques of two prevalent discourses: financialization and ‘privileged intrinsicality’. Financialization reduces everything to a single logic of financial value either in terms of individual income or public savings. Privileged intrinsicality is a nostalgic response to financialization that views education as being valuable in and of itself. Like financialization, it reduces the value of higher education to a single logic of value, only this time, non-financial and ultimately grounded in a particular (liberal) morality. To counter each of these discourses, Downs proposes a form of ‘refraction’ that understands how individual forms of value are always embedded in dominant cultures of valuation. This conception of value as an ongoing process of (e)valuation is referred to as ‘lay normativity’, defined as “that which already and actually matters to people.” (67) This is a reflexive and pragmatic conception of value that is irreducible to a single hegemonic logic and asserts this process of individual and class-based (e)valuation as an expression of agency.

Returning to Rudd and Goodson’s six-point framework for research, they illustrate in their concluding chapter that it takes into account supra, macro, meso and micro levels of analysis, positioning the most abstract level of analysis at the top of the ‘axes of refraction’ (i.e. supra). However, in my view, this methodological separation of the abstract (ideology) from the concrete (individuals) has real, practical consequences in terms of the sixth ‘R’ of resistance. What, exactly, are we resisting? Is it, for example, the supra structures of neoliberalism or the micro agency of Chief Executives? Stephen O’Brien’s chapter on Resisting Neoliberal Education further illustrates this dilemma, where he writes about resisting “these neoliberal times”, resisting a loss of freedom to “an all-consuming capitalism”, and resisting the neoliberal “paradigm”. All of the chapters in the book show a concern with the concrete, qualitative specificity of neoliberalism as well as recognising its abstract nature, which suggests we need a methodology that reveals their inherent unity. One complementary approach is to employ Marx’s dialectical epistemology, which is the basis for his method of “rising from the abstract to the concrete”. For Marx, “the concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many [abstract] determinations, hence unity of the diverse.” (Marx, 1993, 101)

This approach is compatible with Rudd and Goodson’s framework but suggests that the technologies of neoliberalism are the ‘concentration’ of the fundamental (i.e. determinate) categories of capitalism. As a historically specific expression of capitalism (Clarke, 2004), a critique of neoliberalism requires us to understand and work with the analytical categories of critical political economy and in doing so recognise that capitalist society is structured by a quasi-autonomous developmental logic (Postone, 1993) whereby socially constructed abstractions have real, determining, concrete existence and power over people. This logic is laid out in the first chapter of Capital (1976) in Marx’s exposition of the value-form of commodities. It is a form of social domination that extends across all levels of analysis, from supra to micro, and, critically, is given substance and mediated by “the two-fold character of labour according to whether it is expressed in use-value or exchange-value” (Marx, 1987, 402). It is his unique discovery of the dual character of labour in capitalism (and therefore the possibility of its abolition) that fully establishes Marx’s mature work as a theory of emancipation.

Discussions of ‘neoliberal education’ tend to focus on concrete expressions of capitalism (e.g. policy, performativity or professionalism) while rarely engaging with its fundamental categories (e.g. labour, value, capital), let alone being grounded in them (Hall and Downs’ chapters are notable exceptions). As Moishe Postone has argued (1993), one of the problems with this approach is that anti-capitalist efforts to resist the concrete features of neoliberalism tend to be both dualistic and one-sided; they identify capital with its manifest expressions (its concrete appearance rather than essence) and in the act of resistance (e.g. violence, refusal) further hypostasize the concrete while overlooking the fundamentally dialectical nature of capitalism’s social forms and therefore allowing its abstract power to persist unchallenged (Postone, 1980). Thus, efforts to assert an identity and ethic of professionalism, the dignity of useful labour, or indeed, create oppositional alternatives, can themselves be seen as a form of reification which tends to lead to “an expression of a deep and fundamental helplessness, conceptually as well as politically.” (Postone, 2006).

This suggests that the real power of capitalism/neoliberalism is not in the structures of its institutions or the agency of certain individuals to discipline others or undertake acts of resistance, but rather in the impersonal, intangible, quasi-objective form of domination that is expressed in the form of value, the substance of which is labour. What distinguishes this approach from debates that dissolve into metaphysics and morality is that Marx’s category of value refers to a historically specific (i.e. contingent) form of social wealth. As today’s dominant form of social wealth, the form of value as elucidated by Marx (1978) offers the ability to render any aspect of the social and natural world as commensurate with another to devastating effect. The urgent project for education is therefore to support the creation of a new form of social wealth, one that is not based on the commensurability of everything, nor the values of a dominant class, but on the basis of mutuality and love: ‘From each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.’

References

Clarke, Simon (2004) The Neoliberal Theory of Society. In Saad-Filho, Alfredo and Johnston, Deborah (Eds.) Neoliberalism. A Critical Reader. Pluto Press.

Goodson, Ivor F. (2015) The five Rs of educational research, Power and Education 7 (1) 34 – 38

Marx, Karl (1993) Grundrisse, Penguin Classics.

Marx, Karl (1978) The Value-Form, Capital and Class, 4: 130-150.

Marx, Karl (1976) Capital, Penguin Classics.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Frederick (1987) 1864-68, Letters, Marx and Engels Collected Works Volume 42. Lawrence and Wishart Ltd.

Postone, Moishe (2006) History and Helplessness: Mass Mobilization and Contemporary Forms of Anticapitalism, Public Culture, 18 (1) 93-110.

Postone, Moishe (1993) Time, Labour and Social Domination, Cambridge.

Postone, Moishe (1980) Anti-Semitism and National Socialism: Notes on the German Reaction to “Holocaust”, New German Critique, 19 (1) 97-115.

The more radical interpretation of the concept of value…

Source: Simon Clarke (1980), The Value of Value, Capital and Class, 10.

“The more radical interpretation of the concept of value gave it more than a strictly economic significance. Marx’s concept of value expresses not merely the material foundation of capitalist exploitation but also, and inseperably, its social form. Within Marxist economics this implies that value is not simply a technical coefficient, it implies that the process of production, appropriation and circulation of value is a social process in which quantitative magnitudes are socially determined, in the course of struggles between and within classes . Thus the sum of value expressed in a particular commodity cannot be identified with the quantity of labour embodied in it, for the concept of value refers to the socially necessary labour time embodied, to abstract rather than to concrete labour, and this quantity can only be established when private labours are socially validated through the circulation of commodities and of capital . Thus the concept of value can only be considered in relation to the entire circuit of capital, and cannot be considered in relation to production alone.

Moreover neither the quantity of labour embodied in the commodity, nor the quantity of socially necessary labout time attributed to it can be considered as technical coefficients. The social form within which labour is expended plays a major role in determining both the quantity of labour that is expended in producing a commodity with a given technology, and the relation of this quantity to the socially necessary labour time through the social validation of labour time. Finally, the technology itself cannot be treated as an exogenous variable, for the pace and pattern of technological development is also conditioned by the social form of production . Thus consideration of the social form of labour cannot be treated as a sociological study that supplements the hard rigour of the economist, it is inseparable from consideration of the most fundamental economic and even technological features of capitalism.”

…

“If we consider the production and circulation of use-values the two spheres can be defined independently of one another: a certain determinate quantity of use-values is first produced and then exchanged one for another. However as soon as we consider the production and circulation of value, which is the basis for our understanding of the social form of production, it becomes impossible to consider production and circulation independently of one another. Labour time is expended in production, but this labour time is only socially validated in circulation, so value cannot exist prior to exchange, while surplus value depends on the relation between the result of two exchanges (of money capital for labour power and of commodity capital for money) . Thus value cannot be determined within production, independently of the social validation of the labour expended within circulation: circulation is the social form within which apparently independent productive activities are brought into relation with one another and have the stamp of value imposed on them. However value cannot be determined in circulation either, for circulation is the form in which the social mediation of private labours takes place and the latter provide the material foundation of the social determination of value. Thus to isolate production from circulation, even analytically, is to isolate independent productive activities from one another, and so to deprive production of its social form. To isolate circulation from production, on the other hand, is to isolate the social relations between producers from their material foundation. It is in this sense that production and circulation can only be seen as moments of a whole, as the development of the contradictory unity of value and use-value with which Capital begins. The argument holds with added force when we turn to surplus value, and so capital, which depends in addition on the commodity form of labour power.

The idea that the circuit of capital is a totality of which production and circulation are moments is not a metaphysical idea, although Marx does say that the commodity appears to be ‘a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties’ (Capital, I, p. 71, 1967 Moscow edition). The totality is not simply a conceptual totality, an Hegelian idea imposed on reality, it is real and it has a concrete existence. Its reality is that of the class relation between labour and capital, and its existence is the everyday experience of millions of dispossessed workers.”

The value of student loans

Andrew McGettigan, has published another useful post on the complexity of student loans. They are complex, not only for the government to model, but also for the borrower to understand how much they will repay and the actual value of the money they repay. The cost of something worth £9000 today is not the same as paying £9000 for it in ten or thirty years time. Andrew makes that clear in an earlier post.

A website like this one, can help us calculate the effect of inflation on the value of money. It tells me that spending £9000 in 1986 would have bought me the same as spending £24,629 today. In 30 years, the value of money has decreased by nearly two-thirds due to 173% inflation. Inflation in the last 30 years has averaged 3.4%, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator. On that basis, £9000 in cash today will be worth (i.e. have the value of) £3300 in 2046.

In late 2013, I was curious about what the actual total amount of money repaid on full student tuition and maintenance loans would be if I were 18yrs old and planning to go to university in London (where I did my undergraduate degree). When I was 18yrs old, I wouldn’t have asked this question, but now with a fixed term mortgage, where I’m told exactly what I’ll pay back (about double what I borrow), and a young daughter who will probably be going to university in a few years, I’ve become more cautious about long-term repayments on large amounts of money.

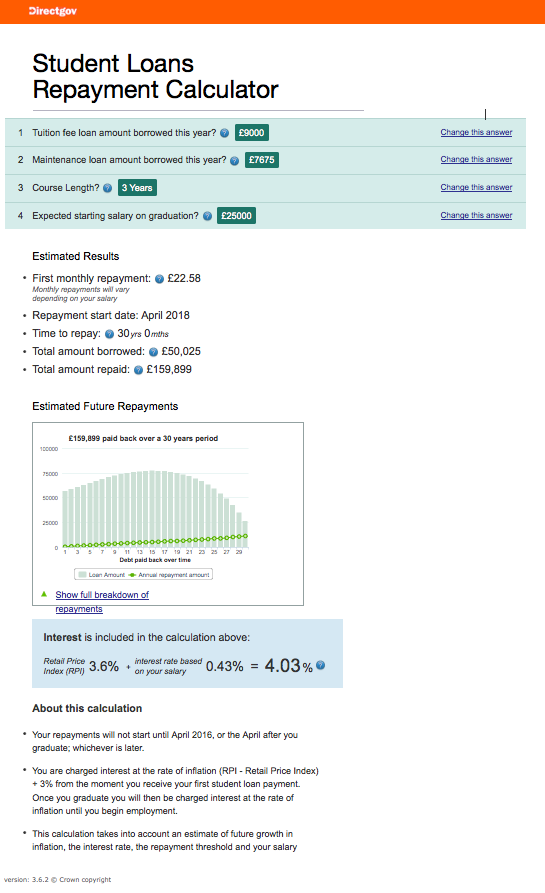

In 2013, I went onto the Directgov website and used their student repayment calculator and you can see that the total amount repaid is estimated by the government to be shy of £160,000. Note the ‘About this calculation’ section at the bottom:

Again, what the calculator does not do is tell you that the value of money goes down due to inflation, so £160K today is not the same amount of money-value as £160K paid back over 30 years.

I just went onto the Directgov website to use their repayment calculator again, but the website is down, perhaps in response to more good work that Andrew did a few weeks ago on ‘Calculator Caveats‘.

A repayment calculator that is working today is on the Compete University Guide website. Punching in the same numbers indicates that I would pay back £81,286 over 30 years, not £160K. However, under the notes they provide, they say the following:

“The level of inflation is difficult to predict, and will vary over the repayment period. Instead of trying to estimate it, we have taken a different approach:

Inflation will affect the fees, the outstanding loan, the interest due, earnings, and repayments to the same extent.

It is therefore not necessary to calculate the interest charges due to inflation. Instead, all monetary figures, including future earnings, are presented in today’s money.”

As a borrower, I’m none the wiser really. What they seem to be saying is that the £81K figure isn’t really what I’ll be paying back because no-one knows what the value of money (and therefore the value of a wage) will be over a given time. I guess it must be somewhere between £81-160K. It certainly isn’t the £44K that has been discussed in the news recently, stating that English student debt is now the highest in the English-speaking world.

The treadmill of capitalism

“In a society in which material wealth is the form of social wealth, increased productivity results either in a greater amount of wealth or in the possibility of a corresponding reduction in labor time. This is not the case when value is the form of wealth. Because the magnitude of value is solely a function of the socially-average labor time expended, the introduction of a new method of increasing productivity only results in a short-term increase in value yielded per unit time – that is, only as long as socially-average labor time remains determined by the older method of production. As soon as the newer level of productivity becomes socially general, the value yielded per unit time falls back to its original level. Thus, because the form of wealth is temporally determined, increased productivity only effects a new norm of socially-necessary labor time. The amount of value yielded per unit time remains the same. The necessity for the expenditure of labor time is consequently not diminished, but is retained. That time, moreover, becomes intensified. The productivity of concrete labor thus interacts with the abstract temporal form in a manner that drives the latter forward while reinforcing the compulsion it exerts on the producers. The value-form of wealth is constituted by and, hence, necessitates, the expenditure of human labor time regardless of the degree to which productivity is developed. The treadmill effect just outlined is immanent to the temporal determination of value. It implies a historical dynamic of production that cannot be grasped when Marx’s “law of value” is understood as an equilibrium theory of the market and when the differences between value and material wealth, abstract and concrete labor, are overlooked. That treadmill dynamic is the initial determination of what Marx developed as central to capitalism: capitalism necessarily must constantly accumulate to stand still. The dynamic becomes somewhat more complicated when one considers capital – “self-valorizing value.” The goal of capitalist production is not value, but the constant expansion of surplus value – the amount of value produced per unit time above and beyond that required for the workers’ reproduction. The category of surplus value not only reveals that the social surplus is indeed created by the workers, but also that the temporal determination of the surplus implies a particular logic of growth, as well as a particular form of the process of production.”

Source: Postone and Brick (1982) Critical Pessimism and the Limits of Traditional Marxism, Theory and Society, 11 (5) 636.

Is student learning a form of labour?

My question is: In undertaking a degree, does a student exchange their labour power for anything? i.e. Is student learning/studying a form of labour? These are just some initial notes. Comments welcome.

Quoting from Chapter 6 of Capital: ‘The Sale and Purchase of Labour-Power’. Translation of online version differs from Penguin Classics/Fowkes version below. My commentary in [parentheses].

“We mean by labour-power, or labour-capacity, the aggregate of those mental and physical capabilities existing in the physical form, the living personality, of a human being, capabilities which he sets in motion whenever he produces a use-value of any kind.”

“But in order that the owner of money may find labour-power on the market as a commodity [from the standpoint of the buyer], various conditions must first be fulfilled. In and for itself, the exchange of commodities implies no other relations of dependence than those which result from its own nature. On this assumption, labour-power can appear on the market as a commodity only if, and in so far as, its possessor, the individual whose labour-power it is [now, the standpoint of the seller – it appears on the market as a commodity but was already a commodity as defined above: as the capability/capacity to produce use-values], offers it for sale or sells it as a commodity. In order that its possessor may sell it as a commodity [implies that labour power is a commodity if the owner is in a position to sell it – not that they do sell it], he must have it at his disposal, he must be the free proprietor of his own labour-capacity, hence of his person. [As the ‘free proprietor’ of his own labour-capacity, the student can choose to give her labour power away for free – sell it for nothing – and even pay the owner of another commodity to assist in enhancing her labour power through education; this is rational under the given circumstances] He and the owner of money meet in the market, and enter into relations with each other on a footing of equality as owners of commodities [money and labour power are both commodities prior to the act of exchange – they both have a value which is measured in socially necessary labour time], with the sole difference that one is a buyer, the other a seller; both are therefore equal in the eyes of the law [this remains true of the student and the teacher]. For this relation to continue, the proprietor of labour-power must always sell it for a limited period only, for if he were to sell it in a lump, once and for all, he would be selling himself, converting himself from a free man into a slave, from an owner of a commodity into a commodity. [The student is an owner of a commodity, not simply a commodity, so they are ‘free’ to dispose of it as they see fit] He must constantly treat his labour-power as his own property, his own commodity, and he can do this only by placing it at the disposal of the buyer, i.e. handing it over to the buyer for him to consume, for a definite period of time, temporarily. In this way he manages both to alienate his labour power and to avoid renouncing his rights of ownership over it. [The student alienates their labour power for a given period during their education and then withdraws it at the end of their education so as to sell it/alienate it on the labour market for a potentially higher price than before their education. We are regularly told that the income of a graduate will be more than the income of a non-graduate over the person’s lifetime and as such, the student will be ‘paid’ for their education].

The second essential condition which allows the owner of money to find labour-power in the market as a commodity is this [again, from the standpoint of the buyer], that the possessor of labour-power [now, standpoint of seller], instead of being able to sell commodities in which his labour has been objectified, must rather be compelled to offer for sale as a commodity [it’s already a commodity before being actually sold – it takes the form of a commodity, regardless of what price/wage it fetches if any] that very labour-power which exists only in his living body [prior to sale, it is objectified as something for sale but not yet alienated; once purchased it is objectified and alienated].

In order that a man may be able to sell commodities other than his labour-power, he must of course possess means of production, such as raw materials, instruments of labour, etc. No boots can be made without leather. He requires also the means of subsistence. Nobody – not even a practitioner of Zukunftsmusik – can live on the products of the future, or on use-values whose production has not yet been completed; just as on the first day of his appearance on the world’s stage, man must still consume every day, before and while he produces. If products are produced as commodities, they must be sold after they have been produced [same with labour power – it must first and always be (re)produced in order to sell], and they can only satisfy the producer’s needs after they have been sold. The time necessary for sale must be counted as well as the time of production. [time studying for the student is (re)productive time as they enhance their labour power]

For the transformation of money into capital, therefore, the owner of money must find the free worker available on the commodity-market [note: not ‘labour market’ since labour-power is simply a commodity, albeit a ‘special’ commodity; the labour market is a commodity market]; and this worker must be free in the double sense that as a free individual he can dispose of his labour-power as his own commodity [the student is ‘free’ to dispose of their labour power in whatever way it may benefit them], and that, on the other hand, he has no other commodity for sale, i.e. he is rid of them, he is free of all the objects needed for the realization of his labour-power. [the student is ‘free’ of the means to enhance their labour power in the way that they deem necessary. Should the means for self-education and social validation become available to them, they may freely choose not to go to university e.g. self-directed learning]

… In order to become a commodity, the product must cease to be produced as the immediate means of subsistence of the producer himself. [here, referring to the production of food, shelter, etc. Historically, such products of labour were not commodities. Higher education enhances labour power; individuals can subsist without it]

… The appearance of products as commodities requires a level of development of the division of labour within society such that the separation of use-value from exchange-value, a separation which first begins with barter, has already been completed. [what was subsistence labour becomes, in an advanced capitalist society, the labour power commodity due to the division of labour/private property]

… This peculiar commodity, labour-power, must now be examined more closely. Like all other commodities it has a value. How is that value determined?

The value of labour-power is determined, as in the case of every other commodity, by the labour-time necessary for the production, and consequently also the reproduction, of this specific article. In so far as it has value, it represents no more than a definite quantity of the average social labour objectified in it. [education adds value, measured by average socially necessary labour time] Labour-power exists only as a capacity of the living individual. Its production consequently presupposes his existence. Given the existence of the individual, the production of labour-power consists in his reproduction of himself or his maintenance. For his maintenance he requires a certain quantity of the means of subsistence. Therefore the labour-time necessary for the production of labour-power is the same as that necessary for the production of those means of subsistence; in other words, the value of labour-power is the value of the means of subsistence necessary for the maintenance of its owner. [hence exploitation being the production of value by labour-power above – surplus to – the necessary labour of the individual] However, labour-power becomes a reality only by being expressed; it is activated only through labour. But in the course of this activity, i.e. labour, a definite quantity of human muscle, nerve, brain, etc. is expended, and these things have to be replaced. Since more is expended, more must be received. If the owner of labour-power works today, tomorrow he must again be able to repeat the same process in the same conditions as regards health and strength. His means of subsistence must therefore be sufficient to maintain him in his normal state as a working individual. [a student must also meet their means of subsistence, the only way being through the sale of their labour power or from gifts, loans, grants, etc. During their education, some students work, most take loans, some use savings, etc. By and large, their subsistence is either based on the sale of past labour power (savings) or future labour power (loans). Full-time study represents a continuity of the expenditure of labour power, despite a suspension of immediate payment for it]

… In contrast, therefore, with the case of other commodities, the determination of the value of labour-power contains a historical and moral element. [the individual is not entirely ‘free’ – the value of their labour power is determined for them and thus the means by which to live] Nevertheless, in a given country at a given period, the average amount of the means of subsistence necessary for the worker is a known datum.

… In order to modify the general nature of the human organism in such a way that it acquires skill and dexterity in a given branch of industry, and becomes labour-power of a developed and specific kind, a special education or training is needed, and this in turn costs an equivalent in commodities of a greater or lesser amount. The costs of education vary according to the degree of complexity of the labour-power required. These expenses (exceedingly small in the case of ordinary labour-power) form a part of the total value spent in producing it. [higher education (re)produces labour power of a developed and specific kind and this has a cost which must be met with an equivalence of other commodities, usually money, though it could be met by an aggregation of different sources]

The value of labour-power can be resolved into the value of a definite quantity of the means of subsistence. [like any individual, a student’s labour power is worth the value of subsistence. How they achieve an exchange for that value is a different matter] It therefore varies with the value of the means of subsistence, i.e. with the quantity of labour-time required to produce them.

… Some of the means of subsistence, such as food and fuel, are consumed every day, and must therefore be replaced every day. Others, such as clothes and furniture, last for longer periods and need to be replaced only at longer intervals. Articles of one kind must be bought or paid for every day, others every week, others every quarter and so on. But in whatever way the sum total of these outlays may be spread over the year, they must be covered by the average income, taking one day with another. [people can subsist for periods of time without the sale of their labour power e.g. loans, charity, but generally speaking these are interim periods made possible by hoards of money – savings/loans – which represent the value of their past/future labour power]

… The ultimate or minimum limit of the value of labour-power is formed by the value of the commodities which have to be supplied every day to the bearer of labour-power, the man, so that he can renew his life-process. That is to say, the limit is formed by the value of the physically indispensable means of subsistence. [again, the student’s subsidized life – gifts, grants, etc. – lessens the value of labour power required for subsistence to the point that its necessary sale can effectively be suspended or covered through part-time work] If the price of labour-power falls to this minimum, it falls below its value, since under such circumstances it can be maintained and developed only in a crippled state, and the value of every commodity is determined by the labour-time required to provide it in its normal quality.

… When we speak of capacity for labour, we do not abstract from the necessary means of subsistence. On the contrary, their value is expressed in its value. If his capacity for labour remains unsold, this is of no advantage to the worker. He will rather feel it to be a cruel nature-imposed necessity that his capacity for labour has required for its production a definite quantity of the means of subsistence, and will continue to require this for its reproduction. Then, like Sismondi, he will discover that ‘the capacity for labour … is nothing unless it is sold’. [A capacity for labour has to be (re)produced one way or another. If it’s not sold today, it must be sold tomorrow or whenever charity/loans are absent. The non-sale of labour power doesn’t negate its existence as a use-value that has an exchange-value i.e. a commodity]

One consequence of the peculiar nature of labour-power as a commodity is this, that it does not in reality pass straight away into the hands of the buyer on the conclusion of the contract between buyer and seller. Its value, like that of every other commodity, is already determined before it enters into circulation, for a definite quantity of social labour has been spent on the production of the labour-power. But its use-value consists in the subsequent exercise of that power. The alienation of labour-power and its real manifestation i.e. the period of its existence as a use-value, do not coincide in time. But in those cases in which the formal alienation by sale of the use-value of a commodity is not simultaneous with its actual transfer to the buyer, the money of the buyer serves as means of payment.

In every country where the capitalist mode of production prevails, it is the custom not to pay for labour-power until it has been exercised for the period fixed by the contract, for example, at the end of each week. In all cases, therefore, the worker advances the use-value of his labour-power to the capitalist. He lets the buyer consume it before he receives payment of the price. Everywhere the worker allows credit to the capitalist. That this credit is no mere fiction is shown not only by the occasional loss of the wages the worker has already advanced, when a capitalist goes bankrupt, but also by a series of more long-lasting consequences. [in the case of the student who receives a loan it is still credit at work but the other way around. The lender allows credit to the student so as to enhance their labour power based on a contract to repay the loan. The contract is based on the student being a private individual who possesses the labour power commodity and therefore is likely to repay the loan. If the student is unable to pay back the loan on the agreed terms, then the lender suffers the consequences]

… Whether money serves as a means of purchase or a means of payment, this does not alter the nature of the exchange of commodities. [student loans and wages for academic labour are both means of payment rather than purchase] The price of the labour-power is fixed by the contract, although it is not realized till later, like the rent of a house. The labour-power is sold, although it is paid for only at a later period. [reinforces the idea that money does not need to be exchanged directly or simultaneously for the expenditure of labour power as a commodity]

It will therefore be useful, if we want to conceive the relation in its pure form, to presuppose for the moment that the possessor of labour-power, on the occasion of each sale, immediately receives the price stipulated in the contract. [as is often the case, Marx is discussing capitalism in its ideal or ‘pure form’ so as to understand its fundamental workings. On the surface, things are more complex – a ‘noisy sphere’ – and it is the job of theory to abstract and bring clarity to complexity]

We now know the manner of determining the value paid by the owner of money to the owner of this peculiar commodity, labourpower. The use-value which the former gets in exchange manifests itself only in the actual utilization, in the process of the consumption of the labour-power. The money-owner [i.e. capital represented by the State and the University] buys everything necessary for this process, such as raw material, in the market, and pays the full price for it. The process of the consumption of labourpower is at the same time the production process of commodities and of surplus-value [the university is a means of production]. The consumption of labour-power is completed, as in the case of every other commodity, outside the market or the sphere of circulation. Let us therefore, in company with the owner of money and the owner of labour-power, leave this noisy sphere, where everything takes place on the surface and in full view of everyone, and follow them into the hidden abode of production, on whose threshold there hangs the notice ‘No admittance except on business’. Here we shall see, not only how capital produces, but how capital is itself produced. The secret of profit-making must at last be laid bare. [the next chapter explains the valorization process which I am not concerned with here. I just want to establish the existence or not of the value-form of the commodity of student labour power]

The sphere of circulation or commodity exchange, within whose boundaries the sale and purchase of labour-power goes on, is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. It is the exclusive realm of Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom,because both buyer and seller of a commodity, let us say of labour power, are determined only by their own free will. They contract as free persons, who are equal before the law. Their contract is the final result in which their joint will finds a common legal expression. Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to his own advantage. The only force bringing them together, and putting them into relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private interest of each. Each pays heed to himself only, and no one worries about the others. And precisely for that reason, either in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an omniscient providence, they all work together to their mutual advantage, for the common weal, and in the common interest. [this paragraph represents the ‘vulgar’ view of capitalist social relations from the ‘noisy’ perspective of the sphere of exchange, i.e. not Marx’s view.]

When we leave this sphere of simple circulation or the exchange of commodities, which provides the ‘free-trader vulgaris’ with his views, his concepts and the standard by which he judges the society of capital and wage-labour, a certain change takes place, or so it appears, in the physiognomy of our dramatis personae. He who was previously the money-owner now strides out in front as a capitalist; the possessor of labour-power follows as his worker. The one smirks self-importantly and is intent on business; the other is timid and holds back, like someone who has brought his own hide to market and now has nothing else to expect but – a tanning.”

[when students study at university and learn from/study with academics, they do so through the exchange of their labour: the commodity of labour power]

Open Co-operatives (2)

In the first part of my notes on ‘open co-operatives’, I focused on Michel Bauwen’s most recent statement, Why We Need a New Kind of Open Cooperatives for the P2P Age. There, he outlines four recommendations for the creation of open co-ops, which are a new synthesis of values and practices of the global P2P, FLOSS and Free Culture movement, with the values, principles and practices of the historic, global co-operative movement. The recommendations are:

- That coops need to be statutorily (internally) oriented towards the common good

- That coops need to have governance models including all stakeholders

- That coops need to actively co-produce the creation of immaterial and material commons

- That coops need to be organized socially and politically on a global basis, even as they produce locally.

Earlier, I made notes on the first two points, suggesting that the co-operative movement indeed already addresses these in quite substantial ways. What appears to be especially novel about Michel’s proposal for ‘open co-ops’ is that the principle and practice of ‘common ownership’ is extended to the product of the co-operative as well as the means of production. This is novel from the point of view of traditional co-operatives, but taken for granted in the world of P2P, FLOSS and Free Culture. However, what that movement lacks is the innovation and experience in developing complementary organisational forms, which the co-operative movement has been working on for over 150 years.

What is also important to note, is that Bauwens regards all of this work on open co-ops, not as the ultimate objective, but as necessarily transitional to the practice of communism, as coined by Marx: ‘From each according to their abilities to each according to their needs’.

Here, I want to focus on Michel’s third recommendation, having just read a number of other articles that discuss the Peer Production ‘Copyfarleft’ License (PPL). More specifically, I consider part (a) of his third recommendation which is intended to address the creation of a self-sustaining immaterial commons. Part (b) of his recommendation, which is the creation of a self-sustaining material commons is not directly addressed here, although many of my comments will be relevant. I will return to this and his fourth recommendation at a later date.

*

The Peer Production License (PPL) was created by Dmytri Kleiner. It is based on the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA v3.0 license and includes an additional restriction (point three below) to those that already exist in the CC license:

- Share-alike/Copyleft: This requires the consumer of the product to license their derivative product under the same terms as the originating product, such that the benefits of each creative work licensed under these terms perpetuate. This resists outright ‘free-loading’ and strategically develops a commons of social property, which is based on a general, indirect degree of reciprocity. This social property is not ‘public’ in terms of regulated by the state, nor individually or collectively ‘private’ as in joint-stock. It is created through what Pedersen (2010) neatly refers to as ‘reciprocity in perpetuity’.

- Non-commercial: The work cannot be used for commercial advantage or private monetary gain i.e. profit. This resists the exploitation of the commons for money, or put another way, it resists the expansion of the value-form of commodities into the money form while still being trapped in the value-form.

- Co-operative: This is an exception to the non-commercial clause above which states that commercial use can be made of the product by democratic, worker-owned organisations that distribute their profits among themselves e.g. co-operatives. This is to allow for and promote the use of the common property of co-operatives in their mutual interest of building a commons. It applies to the immaterial, non-rivalrous knowledge products of the co-operatives. This is the novel addition to the original CC-BY-NC-SA license. It permits a restricted type of commercial use among co-ops while resisting the dissolution of the commons into the anti-social private sphere.

- The producers of the work should be acknowledged: This resists the dissolution of the property into the public domain and ensures that the originating producer(s) are respectfully credited for their contribution. It also adds a dimension of transparency and traceability as to the provenance of each contribution. This is important for a system, such as that proposed by Bauwens and Kleiner, which is based on any kind of reciprocity and equivalence, including that of money.

The PPL license has been discussed in four recent articles:

Miguel Said Vieira & Primavera De Filippi (2014) Between Copyleft and Copyfarleft: Advanced reciprocity for the commons.

Michel Bauwens, Vasilis Kostakis (2014) From the Communism of Capital to Capital for the Commons: Towards an Open Co-operativism.

Stefan Meretz (2014) Socialist Licenses? A Rejoinder to Michel Bauwens and Vasilis Kostakis.

Vieira and De Filippi provide a good discussion of what the PPL offers, the reasoning behind the license, and its advantages and disadvantages. The main advantage, they say, is that the PPL offers a license that sits between standard copyleft (e.g. GPL) licenses and non-commercial copyleft licenses (e.g. CC-BY-NC-SA). 1 Kleiner’s intention in restricting commercial use of the commons property is to restrict its use to those organisations that do not exploit labour (in the technical sense of paying labour less than its actual value) and thereby resist the alienation of labour.

Kleiner is said to have referred (I can’t find a direct reference) to this as the ‘non-alienation clause’. The assumption here is that democratically controlled, worker-owned co-operatives overcome the alienation of wage labour because, in effect, they act as their own capitalist and do not draw a wage as such, but rather they draw from the surplus they collectively make. I have discussed this at length with reference to Jossa’s work on Labour Managed Firms (here, here). Most recently, Jossa has conceded that in fact such firms do not fully overcome alienation, a point that was clear to me from engaging with his earlier work, where I wrote:

“In the absence of the wage-relation i.e. the LMF, workers sell the products that they created and own, rather than sell their labour for a wage. It seems that for Jossa, the key to the capitalist firm and therefore the ‘anti-capitalist’ LMF, turns on how property relations are organised. For Jossa, freedom from capitalism is equated with owning the means of production and from that “decisive” moment, a transition from the capitalist mode of production to the socialist mode of production occurs (Jossa, 2012b:405). For Jossa, once property relations are re-organised in favour of the worker, such that the wage can be abolished, labour is no longer a commodity and its value is no longer measured in abstract labour time because “work becomes abstract when it is done in exchange for wages.” (Jossa, 2012a: 836)”

The problem with Jossa and with the idea of a ‘non-alienation clause’ is that it overlooks or misunderstands the nature of alienation. As I have said before, “What Jossa seems to overlook is that ‘value’, not the wage, mediates labour in a capitalist society.”

In a Preface to Capital, Marx referred to the commodity as the “economic cell-form” from which everything else in capitalist society can and should be examined. According to Marx, in Capital Vol. 1, Ch. 1, a commodity is characterised by having a use-value and an exchange-value. The use-value is the product or service’s utility and the exchange value is its value, or rather the exchange value is the the realisation of the commodity’s value. The value of a commodity is expressed in its exchange value.

Marx said that an understanding of political economy (i.e. capitalism) “pivots” on the understanding of the dual character of labour, as it is expressed in the dual character of the commodity. That is, the use value of the commodity is an expression of the concrete character of labour and the exchange value (value) is the expression of the abstract character of labour. By ‘abstract labour’, Marx was defining the way that value is determined not by the amount of concrete labour that someone put into the production of the commodity, measured by clock time (this was the common view of political economists at that time), but by the homogeneous mass of labour as it exists at any one time as a social whole. This qualitative and commensurable character of labour is quantified, not by clock time, but by ‘socially necessary labour time’, or

“the labour time required to produce any use-value under the conditions of production normal for a given society and with the average degree of skill and intensity of labour prevalent in that society.” (Marx, Capital)

Marx’s discovery was not simply that labour is useful and can be exchanged like any other commodity, but that its character is “expressed” or “contained” in the form of other commodities. What is expressed is that labour in capitalism takes on the form of being both concrete, physiological labour and at the same time abstract, social, homogeneous labour. It is the abstract character of labour that is the source of social wealth in capitalism (i.e. value) and points to a commensurable way of measuring the value of commodities and therefore the wealth of capitalist societies.

What Jossa and perhaps other advocates of worker co-operatives overlook is that in order to understand the social form of wealth in capitalist societies (i.e. ‘value’ ultimately expressed in money), we have to, according to Marx at least, understand the true nature of the commodity as an expression of a particular, historically specific, form of labour which is socially divided by the imposition of private property and other coercive forces; it becomes mediated by value in the form of money, which allows access to that property. Labour should not simply be understood as concrete, physiological labour, but simultaneously as the abstract, social mass of global labour that now extends to most societies across the world. Likewise, the measure of the value of that labour and therefore the commodities it produces, is also characterised by a dynamic, globally determined measure of the social labour time necessary to produce all commodities. In practice, this means that if a person can produce a widget in the Far East in less time than a person in Europe, that efficiency will find its way into determining, through competitive markets, the overall productivity of those widgets and impact on the value of the commodity and therefore the value of the labour in Europe. In this way, as Marx argued, increasing productivity decreases the value of a commodity and pushes down the value and social necessity of labour, rendering an increasing population superfluous to capital’s needs (i.e. under- and unemployment).

As I have argued before,

“In dismissing abstract labour as something overcome in the wage-less Labour Managed Firm, Jossa remains trapped by an economistic understanding of social relations and therefore trapped by value. The same can be said for the worker co-operative form in general. It is a transitional organisational form that moves away from attributes of capitalist labour (towards ownership of the means of production, a democratic division of surplus), but does not in itself overcome the determination of value imposed by the competition of the market.

Freedom is not the emancipation of labour, as in Jossa’s argument, but rather the emancipation from the twofold character of labour, a point also made by Postone, Neary, the Krisis group and others.”

On account of all this, I agree with Meretz‘s excellent critique of copyfarleft, where he concludes:

“Despite all his radical rhetoric, Dmytri Kleiner doesn’t want to touch the basic principles of commodity production. All he wants is a slightly more equal distribution of wealth based on commodity production. This has been the goal of many people, a lot of people have tried to realise it, and despite so many defeats many people still want it. They will not succeed. It is simply not sufficient to achieve workers’ control over the means of production if they go on being used in the same mode of operating. Production is not a neutral issue, seemingly adaptable for different purposes at will, but the production by separate private labour is necessarily commodity production, where social mediation only occurs post facto through the comparison of values – with all the consequences of this – from the market to ecological disaster.”

This is a common critique by Marxists of the potential of worker co-operatives. Effectively, they ‘degenerate’ into capitalist firms (see Egan, 1990) because they are forced to participate in a competitive marketplace alongside traditional capitalist firms. They are accused of focusing too much on the democratic ownership and control of property, while ignoring the fundamental character of the capitalist mode of production. I understand this and agree that it is almost certain to happen. However, does this mean that democratically controlled producer co-operatives are in fact a dead end? I don’t think so and from Bauwen’s text on open co-operatives and other articles I have read, his insistence that P2P and open co-ops are to be understood as ‘transitional’ forms of production and property ownership, suggests that he is also aware of this, but at the same time is concerned with what can be done in today’s historical, material conditions.

We can see this in a more recent exchange between Meretz and Bauwens regarding the Peer Production License. Meretz published a critique of the PPL, in which I think he rightly critiques the notion of ‘reciprocity’ as required by the PPL and Copyfarleft. 2 As I noted above, the value of a commodity is expressed or realised by its exchange value. Marx discussed at length what is meant by exchange value and what is occurring in the act of exchange in capitalism. He referred to this as the ‘value form‘ and with great dialectical rigour, began by discussing it in its ‘simple form’ and then ‘expanded form’, then ‘general form’ and final as the ‘money form’. In effect, he begins by discussing value most abstractly and gradually develops his theory to find its expression in the concrete form of money.

At the heart of the value form (i.e. that which socially characterises value in capitalism), is the idea of equivalence achieved through the exchange of commodities. The value of one or more commodities enters into a relationship with one or more other commodities, whereby each is simultaneously relative and equivalent to the other. The value of one commodity is achieved in its confrontation with another. Meretz understand all of this well and rightly argues that the PPL limits reciprocity while the GPL promotes it. The term ‘reciprocity’ is used by Bauwens and Kostakis to describe a fair exchange between people. Therefore, what makes an exchange under the PPL license reciprocal requires a qualitative understanding of the contribution being made and a quantitative measure of that contribution. This is exactly what, according to Marx, capitalism has achieved in its organising principle of wage labour and private property mediated through the money form. Abstract labour is the qualitative ‘substance’, measured by socially necessary labour time. For Bauwens and Kostakis, it appears that among open co-operatives, this form of exchange is replaced by a more direct form of negotiation:

“the PPL/Commons-based reciprocity licenses would indeed limit the non-reciprocity for for-profit entities, however they would not demand equivalent exchange but only some form of negotiated reciprocity.”

In their paper on the PPL, Vieira and De Filippi attempt to tackle this issue by proposing an alternative or complementary license which better defines the reciprocal contribution required, suggesting that “only those who contribute to the commons are entitled to commercially exploit them – but only to a similar or equivalent extent (i.e. they can take only as much as they have given to the commons).” They then go on to propose a non-circulating “peer-currency” system of tokens. They argue that their additional reciprocity clause “introduces an expectation of ‘advance reciprocity’… because every entity has to contribute beforehand in order to obtain tokens and thus make commercial uses of the commons.” The result of this, they suggest, is that “large corporations such as Google or Facebook will only be able to use their work to the extent that they contribute back to the commons – either by producing and contributing for the commons in order to obtain credits, or by paying the proper licensing fees.”

To be honest, I don’t know what to make of this. On the face of it, it seems absurd to me since we already have a token system intended to ensure equivalent reciprocity: Money. I also can’t see how it changes anything in terms of the large corporations benefiting more from the work of smaller producers since a large corporation can afford to make their like-for-like contribution quite easily, whereas it would be very difficult for a small worker co-op to match the contribution of the large corporation – reciprocity extends both ways. Anyway, putting that aside, a system of non-circulating tokens is something that Marx suggested might be necessary in the transition towards full communism, as he recognised that during this transitional state, people would still expect to receive an equal amount back in return for their labour:

“Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society — after the deductions have been made — exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labor. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labor time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labor (after deducting his labor for the common funds); and with this certificate, he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labor cost. The same amount of labor which he has given to society in one form, he receives back in another.

Here, obviously, the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is exchange of equal values. Content and form are changed, because under the altered circumstances no one can give anything except his labor, and because, on the other hand, nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals, except individual means of consumption.

But as far as the distribution of the latter among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form”

When Bauwens and Kostakis state, “A commons-based reciprocity license would simply ask for reciprocity”, I think they are underestimating the difficulty of achieving this in practice. Not only that, but the GPL and other Copyleft licenses have taken us beyond the point of requiring reciprocity. Further on in their article, critically discussing the GPL, they refer to

“what anthropologists call ‘general reciprocity’, that is at the collective level, a minimum of contributions is needed to sustain the system. Nevertheless there is absolutely no requirement for direct reciprocity. The reciprocity is between the individual and the system as a whole.”

My view, and I think it is Meretz’s too, is that this is actually a very positive thing, which from an understanding of the value-form, moves us away from the imposition of equivalence on all aspects of social life. Yet, against the GPL, Bauwens and Kostakis are arguing for a more “direct” form of reciprocity which would be enforced by the PPL.

As I said in my first set of notes on open co-ops: Reciprocity is the logic of (imposed) scarcity. Non-reciprocity is the logic of abundance. Although Meretz goes on to define a distinction between ‘positive reciprocity’ and ‘negative reciprocity’, I don’t think this is helpful. The aim should be to altogether overcome the compulsion of reciprocity, which is the logic of poverty, protected by law.

“In modern society, where the conditions of life are private property, needs are separated from capacities. A state of abundance would alter this. Needs and capacities would come together, and close off the space between them. In modern society, this space is filled by the dense structures of private property-political order and the law of labour: in a state of abundance they would have no place. If the productive capacities already deployed were oriented towards need, necessary labour would be reduced to a minimum, so that nothing would stand between men and what they need to live. Money and the law of labour would lose their force, and, as its foundations crumbled, the political state would wither away. The state of abundance is not a Utopian vision but the real possibility of conditions already in existence.” (Kay and Mott 1982)

Yet, again I am reminded of Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, where he recognises that the material premises have to be in place and apparent to the majority of individuals in society in order for the logic of the former social conditions to be abandoned:

“Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.”

The GPL is a license that recognises the premise of abundance in the immaterial social realm, where the notion of “each to each” can exist in practice. Although still an expression of liberal capitalist jurisdiction, it is an expedient means towards developing and demonstrating the premises for communism. My view is that for the immaterial commons, the GPL remains adequate to the task of growing that commons – criticisms of it being non-reciprocal are confusing reciprocity with equivalence, which is one of the reasons we should be against reciprocity altogether.

The ‘communistic’ nature of the GPL has been discussed at length by Jakob Rigi, who also bases his argument on the theoretical and methodological foundations developed by Marx. In his response, he states:

“I commend Bauwens & Kostakis for their activist approach and their good intentions to develop an alternative to capitalism and establish an ethical economy. Unfortunately, however, their approach not only fails to achieve these goals, but perpetuates capitalism.” (2014: 393)

He argues that Bauwen and Kostakis’ desire (as expressed in the PPL) to retain the essential categories of capital (e.g. surplus value, profit) only perpetuates capitalism. Rigi goes into great detail in his discussion about how co-operatives are trapped by the logic of capitalism and must at some point degenerate, die, or overcome the necessity of commodity production. On this, he agrees with Meretz:

“To sum up the cooperative is implicated in the capitalist mechanism of exploitation either as an exploited or exploiting party in the both processes of the formation of values and that of the production prices of the commodities they produce. A single commodity is a social interface (relation) in a double sense. On the one hand as a value bearing entity it is an interface between all labour that produces that type of commodity. And on the other, as a price bearing entity it is an interface between all constituent elements of the total social capital, i.e. the capitalist economy as a whole. No magic of cooperation can change these realities. The only way for cooperatives to break with the logic of capital is to break with the market, i.e. not to produce commodities.” (Rigi 2014: 395)

Rigi provides a good discussion on the parasitic nature of rent, arguing that knowledge products, e.g. software, literally have no value, and that along with interest on capital, rent should be part of the total abolition of capitalism. He agrees that “the idea of peer-producing cooperatives as a platform for launching peer-production is appealing. But these cooperatives’ main direction should be to work against the market and money and break with them.” (397)

In principle, I agree, but Rigi’s critique remains adhered to a traditional view of worker struggle against capital and overlooks the implications of his own explanation of the labour theory of value. He begins his critique of Meretz’s rejoinder to Bauwens and Kostakis by stating:

“I agree with most of Meretz’s criticism of Bauwens & Kostakis. However, I find two problems in his rejoinder. His distinction between exchange and reciprocity is not helpful. Second, he does not grasp the GPL’s communist nature and its revolutionary-transformative historical potentials..” (398)

Likewise, I agree with most of Meretz’s criticisms, too, but as with Meretz, a problem remains with Rigi’s understanding of reciprocity in terms of capitalist exchange, too.

“Of course, Meretz is correct that the GPL as a license is a contract, a juridical form, a social rule and not immediately reciprocity. But this contract stipulates a universal reciprocity, and in this sense it is communistic. Communism is nothing but universal reciprocity… Communism is nothing but realization of individual potentials through voluntary participation in social production and making the product available to all members of society regardless of their contributions.” (398-9)

To develop his argument around reciprocity and exchange, Rigi draws on the work of Marshall Sahlins (1974). He states that Sahlins’ study of ‘Stone Age Economics’ distinguished between three different types of reciprocity: “negative (commodity exchange), balanced (gift exchange) and general reciprocity.” Bauwens and Kostakis regard the GPL license as promoting ‘general reciprocity’, where “there is no logic of equivalence, you give without expecting to receive something back directly.” (Rigi 2014: 398) Rigi argues that the GPL does not fit any of Sahlins’ forms of reciprocity because,

“the giver always receives back something larger (the whole im- proved software = the sum of all contributions) of what s/he gives (her/his contribution). On the other hand the receiver is not obliged to contribute, i.e. s/he receives the sum of all contributions without being obliged to contribute as long as s/he does not publish the derivative. We may call this a communist form of reciprocity.” (398)

Just as Meretz wants to distinguish between positive and negative forms of reciprocity, Rigi is also unable to abandon the idea and creates another sub-category of reciprocity, too. As I stated above, it is my view that, according to Marx’s labour theory of value, communism is the overcoming and negation of the conditions that require reciprocity (i.e. scarcity and poverty) and that “each according to each” describes a social world where no concern for reciprocity remains.

Both Meretz and Rigi understand the centrality of the mode of production in capitalism, over and above the mode of distribution. Both authors understand Marx’s labour theory of value, too. Yet both critics of the PPL and open co-operatives, fall back on a critique of exchange and distribution, rather than fully engaging in a critique of production.

Why is it so difficult for us to abandon the idea of reciprocity in a future society of abundance? Sahlins’ ‘negative’, ‘balanced’ and ‘general’ forms of reciprocity are each conditioned by specific, historical modes of production and their subsequent social customs. It is impossible to determine the precise nature of communist, or post-capitalist society but according to Marx, we can say that ‘post-capitalism’ points to a society where value has been abolished as the form of social wealth.

What does it mean to abolish value? It means that the ‘value form’ (the exchange of relative and equivalent use-values) no longer mediates our social relations as it does today and this means that our social relations are no longer determined by the ‘commodity form’ (the necessity to produce use-values primarily for exchange-value). And because the commodity form is nothing more than the expression of the dual character of labour (concrete and abstract labour), we find that the abolition of value is in fact the abolition of labour, or rather capitalism’s dual form of labour. Since it is absurd to suggest that any future society would abolish the physiological requirement of usefully expending energy, the abolition of labour is not the abolition of concrete useful labour, but the abolition of the abstract, social, homogeneous form of labour brought about due to the division of labour and its corresponding institution of private property. With this uniquely capitalist qualitative form of labour abolished, so would its measure (and therefore the measure of value) of ‘socially necessary labour time’ be overcome, too. In moving towards such a society, labour, according to Marx, would transition gradually from being indirect as it is now, mediated by exchange, to being ‘direct labour’, characterised not by reciprocity, but by the custom of “each according from their ability to each according to their own.” Such a social custom is not the product of the creation of a new form of exchange, but rather a new mode of production based on freely associated concrete labour. Freedom then, is freedom from abstract labour measured by socially necessary labour time (i.e. freedom from value). That ‘freedom’ from abstract (wage) labour is currently being objectively imposed on the under and unemployed. The challenge for the open co-operative movement is to create a new, sustainable form of social wealth, built upon the general social knowledge developed through the capitalist mode of production, such that we might be fortunate enough to abandon the capitalist social factory altogether.

Elsewhere (and here), I have highlighted the importance of Peter Hudis’ recent work in understanding Marx’s views on post-capitalism. I think it is especially valuable in thinking about the issues I have discussed around ‘open co-operatives’ not least because his work recognises both the necessity of abolishing value, but also the importance of worker co-operatives as a means to achieve that aim.

Hudis, quoting Marx, notes that in the transition to post-capitalism “social relations become ‘transparent in their simplicity’ once the labourers put an end to alienated labour and the dictatorship of abstract time.”

“Marx is not suggesting that all facets of life become transparent in the lower phase of socialism or communism; indeed, he never suggests this about conditions in a higher phase either. He is addressing something much more specific: namely, the transparent nature of the exchange between labor time and products of labor. This relation can never be transparent so long as there is value production; it becomes transparent only once indirectly social labour is replaced by directly social labour.” (209-10)

Direct labour then, is a transparent process instead of the opaque process of indirect, value-creating, alienated capitalist labour. The conditions for this form of labour do not simply come about by wishing for them or even demanding them, but are the outcome of historical conditions of production, as Hudis explains:

“Marx does not, of course, limit his horizon to the initial phase of socialism or communism. He discusses it as part of understanding what is needed in order to bring to realization the more expansive social relations of a higher phase. Marx conceives of this phase as the passing beyond of natural necessity—not in the sense that labor as such would come to an end, but rather that society would no longer be governed by the necessity for material production and reproduction. This higher phase, however, can only come into being as a result of a whole series of complex and involved historical developments, which include the abolition of the “the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and thereby also the antithesis between mental and physical labor.” It is impossible to achieve this, he reminds us, in the absence of highly developed productive forces. Marx never conceived it as possible for a society to pass to ‘socialism’ or ‘communism’ while remaining imprisoned in conditions of social and technological backwardness. And yet it is not the productive forces that create the new society: it is, instead, live men and women.” (210)

Direct labour is made possible by the human development of productive forces that provide the requisite conditions of abundance so that the conditions of material and therefore social necessity are surpassed and we are no longer subordinated to the necessity of the division of labour in order to achieve such levels of productivity and abundance. Capitalism has achieved the current levels of productivity and abundance precisely through co-operation, which Marx called the the “fundamental form of the capitalist mode of production.”

“When numerous labourers work together side by side, whether in one and the same process, or in different but connected processes, they are said to co-operate, or to work in co-operation… Co-operation ever constitutes the fundamental form of the capitalist mode of production.” (Marx, Capital Vol.1, Ch. 13)

We should be mindful that ‘co-operation’ is fundamental to the capitalist mode of production in that it represents the socialisation of labour that has been divided and alienated from its product. In their earlier work, Marx and Engels explicitly argued for the abolition of the division of labour. For example:

“We have already shown above that the abolition of a state of affairs in which relations become independent of individuals, in which individuality is subservient to chance and the personal relations of individuals are subordinated to general class relations, etc.—that the abolition of this state of affairs is determined in the final analysis by the abolition of division of labour. We have also shown that the abolition of division of labour is determined by the development of intercourse and productive forces to such a degree of universality that private property and division of labour become fetters on them. We have further shown that private property can be abolished only on condition of an all-round development of individuals, precisely because the existing form of intercourse and the existing productive forces are all-embracing and only individuals that are developing in an all-round fashion can appropriate them, i.e., can turn them into free manifestations of their lives. We have shown that at the present time individuals must abolish private property, because the productive forces and forms of intercourse have developed so far that, under the domination of private property, they have become destructive forces, and because the contradiction between the classes has reached its extreme limit. Finally, we have shown that the abolition of private property and of the division of labour is itself the association of individuals on the basis created by modern productive forces and world intercourse.” (More examples here)

So, to return to my question above: Why is it that even Marxists, who have a grasp of the labour theory of value, end up arguing for new forms of distribution to supersede the existing form?

The essential work of Historian, Moishe Postone, provides an answer: