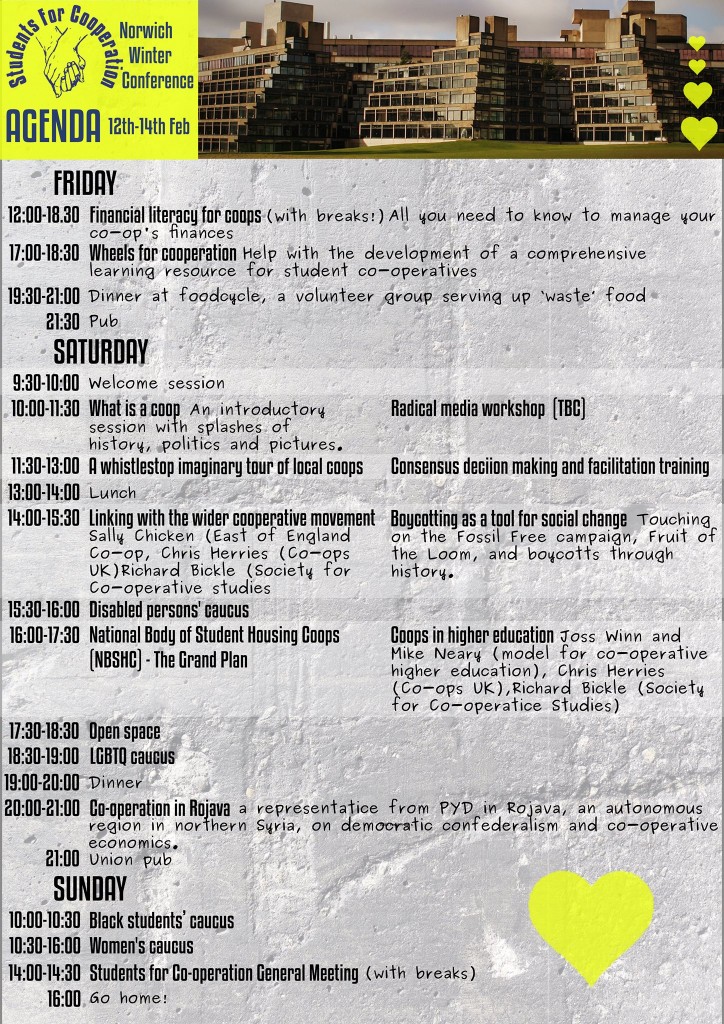

Following on from a conference paper that I wrote in late 2014, I have been thinking more about the ‘social’ (Italy) or ‘solidarity’ (Canada) or ‘multi-stakeholder‘ (UK) form of co-operative as a constitutional and organisational form for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs).

The corporation

To begin with, I have been thinking about the chapter in Marx’s Capital Vol.3 where he discussed the role of credit, and in that chapter also discusses the (relatively new at the time) form of ‘joint-stock’ companies. What we call ‘corporations‘ today are the modern day version of this form of company, characterised by the socialisation of capital among multiple capitalists, united under the single legal personality of the corporation, with limited liability for its assets. It’s Marx’s emphasis that the corporate form represents not simply the concentration of capital (tending towards monopolies), but also the socialisation of capital as it does away with the individual private capitalist.

Although the term ‘corporate’ often has negative connotations today, Marx understood incorporated joint-stock companies as a historically progressive form of association, to the extent that he thought they were evidence of “the abolition of capital as private property within the framework of capitalist production itself.” Marx gives four reasons why joint-stock companies were historically progressive:

- By combining their individual capital and creating a form of “social capital”, capitalists could scale up their endeavours and produce at much larger scales, even taking on some of the services that the state provided.

- The combination of social capital with the already social mode of production, and the concentration of the social means of production, results in a shift from private undertakings to social undertakings i.e. “the abolition of capital as private property within the framework of capitalist production itself.” Individual capitalists no longer compete with each other, but form share-holding groups of capitalists who compete as single corporate personalities.

- The individual capitalist can no longer point to his or her individual capital, but becomes instead a “mere money capitalist”. The “actually functioning capitalist” is the “mere manager, administrator of other people’s capital”, who like the worker is alienated from the means of production. Marx regarded this as “the ultimate development of capitalist production” and “a necessary transitional phase towards the reconversion of capital into the property of producers, although no longer as the private property of the individual producers, but rather as the property of associated producers, as outright social property.”

- The means of production no longer belongs to the individual capitalist, but is rather the social capital of the “association of producers” (shareholders). As such, no individual owns the means of production as it is the “social property” of the owners of capital (the “money capitalists”). However, it is an “appropriation of social property by a few” rather than by the majority (the workers, managers, administrators, etc.) The corporate form of joint-stock companies still remains “ensnared in the trammels of capitalism”. It may be a progressive, transitional form of association, but does not overcome the antithesis between social and private wealth.

However, Marx finishes the chapter by pointing to another new form of association: the worker co-operative. It is better I just quote the whole paragraph here:

“The co-operative factories of the labourers themselves represent within the old form the first sprouts of the new, although they naturally reproduce, and must reproduce, everywhere in their actual organisation all the shortcomings of the prevailing system. But the antithesis between capital and labour is overcome within them, if at first only by way of making the associated labourers into their own capitalist, i.e., by enabling them to use the means of production for the employment of their own labour. They show how a new mode of production naturally grows out of an old one, when the development of the material forces of production and of the corresponding forms of social production have reached a particular stage. Without the factory system arising out of the capitalist mode of production there could have been no co-operative factories. Nor could these have developed without the credit system arising out of the same mode of production. The credit system is not only the principal basis for the gradual transformation of capitalist private enterprises into capitalist stock companies, but equally offers the means for the gradual extension of co-operative enterprises on a more or less national scale. The capitalist stock companies, as much as the co-operative factories, should be considered as transitional forms from the capitalist mode of production to the associated one, with the only distinction that the antagonism is resolved negatively in the one and positively in the other.”

The worker co-operative then, is also a transitional form of association that socialises property and goes one stage further than joint-stock companies by socialising the ownership of capital among the association of producers/workers. Within the historical limits of the 19th c. “prevailing system”, worker co-operatives represented the most progressive form of capitalist association where the ownership of, the means of, and the mode of production were social and not individual/private. Marx is clear that it is only because of the capitalist mode of production that worker co-operatives could develop and the worker co-operative, too, is a transitional form that will “sprout” something new.

The point I am trying to make in this rather long introduction, is that with the movement of time, we should expect to see new forms of association emerge, made possible by earlier forms, if only through attempts to resolve their contradictions. During Marx’s time there were ‘consumer’ and ‘producer’ (i.e. worker) co-operatives and these two types of co-operative are now widespread across the world. Neither of these forms of association have so far been adopted as the form of association for a university 1, but a more recent co-operative form has been applied in higher education: the social/solidarity/multi-stakeholder co-operative (from hereon, the ‘social co-operative’).

Social co-operatives as a new, transitional form

Social co-operatives are a historically recent form of association, emerging in the 1970s, gradually obtaining legal status in some countries. In 2011, the ‘World Standards of Social Co-operatives’ was ratified after a two-year global consultation process. So we are dealing with a new form of association that was not available to Marx or to the founders of most 20th century universities. To my knowledge, only one such university exists: Mondragon, in the Basque region of Spain, where its membership is comprised of workers (academics and non-academic employee-owners), students, and ‘collaborators’ (members of the community, local business, etc.) In its current form, Mondragon University only dates back to 1997.

If you read the World Standards of Social Co-operatives, you’ll see there are essentially five defining characteristics of social co-opertives, at the heart of which is the multi-stakeholder membership structure. Social co-operatives are therefore distinct from the traditional ‘worker’ or ‘consumer’ co-operative forms, which recognise just one membership type. The ‘social co-operative’ typically incorporates three membership types: worker, user/consumer, and supporter, thereby acknowledging the different ‘stakes’ that a community of people may have in the co-operative and the shared interests of all member-types in the mission and sustainability of the organisations. 2

‘Social co-operatives’ are constitutionally democratic forms of enterprise comprising two or more types of membership. Each of the stakeholder groups is formally represented in the governing structures of the organisation on the basis of one-person one-vote. Legal recognition for social co-operatives was first achieved in Italy in 1991, and in the UK, such ‘multi-stakeholder co-operative societies’ are now regulated by the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014 or the Companies Act 2006. The multiple forms of membership reflect the combined interests of the organisation within its social context and not surprisingly, social co-operatives typically pursue social objectives through the provision of social services, such as healthcare and education. For example, since 2011, over 850 schools in the UK have become multi-stakeholder co-operatives. This particular model of democratic ownership and governance is an increasingly popular form of co-operative organisation and there are successful examples of different sizes and services provided, demonstrating its flexibility as a modern organisational form.

University governance: Still ‘not fit for modern times’?

A glance at the literature on university governance in the UK shows that a number of incremental policy changes have led to a more widespread corporate form of university governance, starting with the Jarratt report (1985), which established the Vice Chancellor as Chief Executive, then the Dearing report (1997), which reduced the number of members on the governing body, and the Lambert report (2003), which stated that participatory governance by a community of scholars was not ‘fit for modern times’, and recommended a voluntary code of governance for the HE sector (Shattock, 2006). Each of these government sponsored reviews and subsequent policy and regulatory changes has been conducted in response to the changing historical context of the corporate form in general, most notably the Cadbury report (1992), the Hampel report (1998), the Higgs report (2003) and the development of the current UK Corporate Governance Code (Shattock, 2006). Thus, a history of the development of university governance and management has to be seen in the broader context of changing corporate forms and the underlying dynamic of political, economic and social contradictions.

Universities have historically been established in different legal forms but since the 1988 Education Reform Act, most new universities have been established as Higher Education Corporations (HEC). This is changing yet again, as the most recent regulatory changes since the Browne review have been to encourage the more rapid establishment of new forms of higher education providers with degree awarding powers (so-called ‘new entrants’ to the market), including for-profit private institutions. 3

What we need is a clear and coherent picture of university governance from a historical perspective and to introduce the ‘social co-operative’ as a new historical form of institutional governance that appears to be compatible with collegial structures (Cook, 2013) and speaks to many of the concerns raised over increased corporate governance structures and hierarchical management of universities (Bacon, 2014) by providing an alternative for existing governors, academics and students to consider. Until recently, universities in the UK have been neither publicly or privately owned corporations. The so-called ‘public universities’ in the UK are effectively owned by their current governors. What we need, I think, is to encourage a different way of thinking about the role, value and form of higher education institutions in society as ‘social’ organisations sustained through solidarity and co-operation among their members. We need to acknowledge that current hierarchical and undemocratic models of governance alienate and de-motivate university staff (Bacon, 2014) and that co-operative values and principles are attractive to both staff and students (Cook, 2013). We need to compare forms of governance in both higher education and social cooperatives and use this as a stimulus for critical reflection on the practical and contemporary issue of democracy in higher education. I think we need to respond to the growing ‘democratic deficit’ in higher education (McGettigan, 2014), by questioning university governance in light of constitutional innovations in cooperative organisations.

Back to Marx

As I indicated in the first section of these notes, I think a history of university needs to be undertaken from the perspective that Marx provides; that is, a view of organisations as social forms of capital that is becoming increasingly social, past the point of private property and joint stock to common forms of ownership. We are now past the point that worker co-operatives reached by reversing the relation between labour and capital because the social co-operative form has extended democratic control and common ownership of capital beyond worker members of the co-operative to include users/consumers and other beneficiaries (which could include representatives of the state/public).

Peter Hudis notes that Marx regarded worker co-ops as a new form of production, whereas joint-stock firms were the highest form of capitalist production. (Hudis, 2011, 179) The socialisation of property that the joint-stock firm represents is only that. It did nothing to change the relation between capital and labour, whereas worker co-ops turn the capital relation on its head. Yet worker co-ops, because of their single-member character, are still limited by the fact that they are subject to value production through the exchange relation: Workers are producers who require consumers. They do not produce goods and services to directly satisfy their own needs. “In this sense”, write Hudis, “they still remain within capitalism, even as they contain social relations that point to its possible transcendence.” (180)

Does the social co-operative form represent a further progression towards the transcendence of capitalism? A social co-operative, at least in an ideal sense, is a form of association owned in common and democratically controlled by both producer and consumer members, establishing a direct satisfaction of needs between members. To what extent this overcomes the value-form relation of exchange is not entirely clear to me at this point. Value production still determines the social co-operative in its members’ relations with other firms, with whom they enter into exchange relations, but to what extent does exchange (i.e. for the purpose of exchange value) take place between members of the commonly owned social co-operative? Is the product or more often the service that the social co-op produces a ‘commodity’ as defined by Marx? Is the use value of that service being produced by workers who are alienated from the means of production for the primary purpose of exchange? It doesn’t seem like it to me. A better question might be: does the labour performed by workers in the social co-op take the dual form of concrete and abstract labour? Yes, to the extent that the wider social relations of value production in capitalist society continues to determine their needs.

I am not suggesting that the social co-operative form overcomes the capitalist form, but that it might represent an advanced transitional form of social association between individuals. I think that the social co-op goes further than the worker co-op form in constituting a dialectical response to capital and a more socially encompassing “safe space” (Egan, 1990) against the determinate logic of value. Egan, referring to worker co-ops, concludes that the ‘‘potential for degeneration [of worker co-ops into capitalist firms] must be seen to lie not within the cooperative form of organisation itself, but in the contradiction between it and its capitalist environment. Degeneration is not, however, determined by this contradiction’’ (1990, 81). It seems to me that the social co-op form extends the “safe space” to include direct exchange between producers and consumers (who are ultimately owners of common capital) and has greater potential to resist degeneration.