Below is a blog post I wrote for the Times Higher Education. It was edited for publication and may require registration on THE to view it, so is presented here in its original form.

Last week, the Co-operative College, established in Manchester in 1919, hosted a conference on ‘Making the Co-operative University’ with the intention of exploring its role in supporting and co-ordinating a federated model of co-operative higher education.

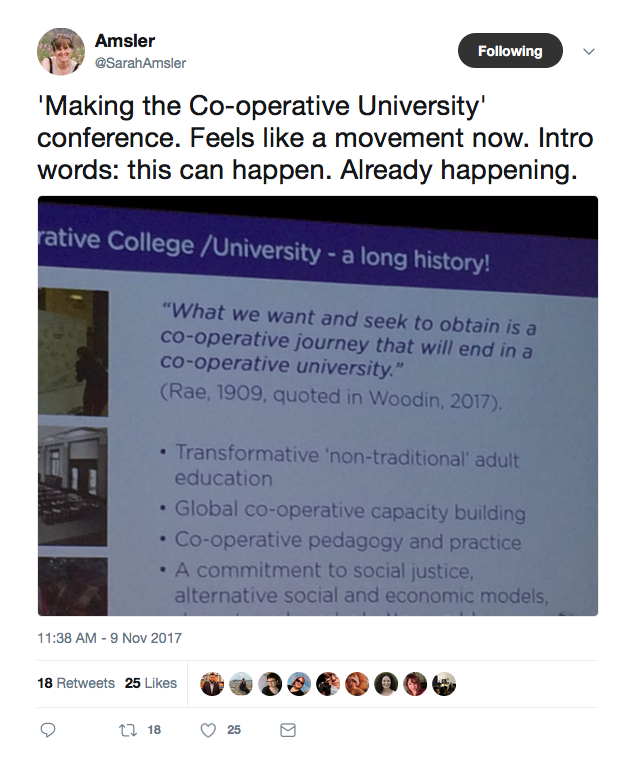

Throughout the day, there was a sense of anticipation and historic responsibility among the 90 delegates who were told that in 1909, W. R. Rae, Chair of the Co-operative Union educational committee, had addressed the Union and stated that “What we want and seek to obtain is a co-operative journey that will end in a co-operative university”. Writing at a time when there were only 15 universities in the UK, Rae saw the development of a co-operative university as another example of members providing for themselves where the State did not: “So long as the State does not provide it, we must do, as we have in the past, the best we can to provide it ourselves.” Over the last century, the State has provided a higher education that may have satisfied Rae, but the tripling of tuition fees in 2012 and the incremental corporatisation and marketisation of higher education since the 1980s have angered students, academics and administrators. Once again the co-operative model of democratic member control is being identified as a necessary intervention where the State is failing to provide.

Indeed, the “historic” nature of the event was preceeded by a recent decision by the Co-operative College’s Board of Trustees who committed its members to explore a federated co-operative university and all of its possibilities. The federated model of co-operative solidarity is not unusual among co-operatives. In 1944, the College wrote about how it “could become the nucleus of a Co-operative University of Great Britain, with a number of affiliated sectional and regional Colleges or Co-operative institutes, as the demand arises.” In fact, as the Times Higher Education has previously reported, Mondragon University in Spain already exists as a federated co-operative university with a small number of staff serving four autonomous worker co-operative Faculties with hundreds of academics and thousands of students.

Jon Altuna, the Vice-Rector of Mondragon University gave a pre-recorded interview for the conference, helping establish how and why the university was set up and the way it is run. Alongside Mondragon were presentations from other groups and organisations that are seeking to provide or already providing co-operative forms of higher education: The Centre for Human Ecology, founded in 1972; The Social Science Centre, Lincoln , a co-operative for higher education set up in 2011; Free University Brighton, running since 2012; Students for Co-operation, a national federation of student co-operatives established in 2013 that supports 24 food co-ops and four housing co-ops; RED Learning Co-operative, a new co-op set up by ex-Ruskin College academics to provide training and education to the Labour Movement and other activists; and Leicester Vaughan College, established in 1862 to provide adult education but recently “disestablished’ by Leicester University and re-established as a co-operative by its staff and local supporters, including the city council.

The diversity of these initiatives was celebrated at the conference for meeting local and unmet needs in adult education, while at the same time recognising the limitations of working on the fringes: too much reliance on voluntary labour, insufficient funds and the difficulty of being accredited by an external awarding body. This is where the Co-operative College comes in.

The conference was a pivotal event that came about through the efforts of a Co-operative University Working Group (of which I was a member) that was set up to pull together the work that has been done around co-operative higher education over the last the last few years and advise the Board of Trustees on the feasibility of the College acting as co-ordinator and accreditor for autonomous co-operatives offering degrees or degree-level courses. Looking ahead, the conference also aimed to establish a Co-operative Higher Education Forum that could replace the Working Group and be open to anyone interested in co-operative higher education. Representatives from the Forum will advise the College’s newly established Academic Board on the direction to take.

After presentations from people in the morning, the afternoon of the conference focused on thematic discussions around Democracy, Members and Governance; Knowledge, Curriculum and Pedagogy; Livelihood and Finances; and Bureaucracy and Accreditation. While not determining the final outcome, there does seem to be a direction of travel for co-operative higher education in the UK: It is likely to be based on the principle of subsidiarity, with democratic control in the hands of the people most affected; membership will be open and voluntary and meaningfully linked to the system of governance providing all members, students, academics, administrators, with equal powers. Teaching and learning will draw from traditions of adult, community and participatory education, involving students and academics in a combined culture of research and teaching. Co-operatives are ‘enterprises’ run by and for their members and there is a recognition that members have to face the risks and challenges of creating sustainable business models that draw on the existing co-operative commonwealth and sources of public funding. Perhaps the greatest unknown at this time is what the relationship between the co-operative movement and the state regulator will look like.

The Co-operative College are meeting with HEFCE this month to understand the current regulatory landscape following the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 and are poring over the recently published consultation documents to understand the implications of the new regulator, the Office for Students. If the key requirements of demonstrably good governance, a good quality education, and a sustainable financial model remain the basic threshold for gaining Degree Awarding Powers then there is no reason why Co-operatives, operating on 180 year-old, values-based principles of social organisation, can’t meet those requirements in ways that challenge the existing system of higher education in England with a real alternative.

4 thoughts on “Making the co-operative university”