UPDATE 02/02/15

We’ve received and accepted some excellent responses to this CfP but we’re hoping for more. Consequently, the deadline for abstracts has been extended until the 1st March. All other dates remain the same.

If you’re thinking of submitting an abstract please note that we’re specifically looking for “…papers that acknowledge the foundational work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels for labor theory and engage closely and critically with the critique of political economy.”

Where we’ve had to decline a submission it’s because the author has not made clear how they intend to engage with Marx and Engels’ work at the level that we’re seeking for this special issue. If in doubt, feel free to get in touch. Thank you.

===

Karen Gregory and I will be guest editors for a special issue of Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor. Here’s the Call for Papers [download for printing]:

Marx, Engels and the Critique of Academic Labor

Special Issue of Workplace

Guest Editors: Karen Gregory & Joss Winn

Articles in Workplace have repeatedly called for increased collective organisation in opposition to a disturbing trajectory: individual autonomy is decreasing, contractual conditions are worsening, individual mental health issues are rising, and academic work is being intensified. Despite our theoretical advances and concerted practical efforts to resist these conditions, the gains of the 20th century labor movement are diminishing and the history of the university appears to be on a determinate course. To date, this course is often spoken of in the language of “crisis.”

While crisis may indeed point us toward the contemporary social experience of work and study within the university, we suggest that there is one response to the transformation of the university that has yet to be adequately explored: A thoroughgoing and reflexive critique of academic labor and its ensuing forms of value. By this, we mean a negative critique of academic labor and its role in the political economy of capitalism; one which focuses on understanding the basic character of ‘labor’ in capitalism as a historically specific social form. Beyond the framework of crisis, what productive, definite social relations are actively resituating the university and its labor within the demands, proliferations, and contradictions of capital?

We aim to produce a negative critique of academic labor that not only makes transparent these social relations, but repositions academic labor within a new conversation of possibility.

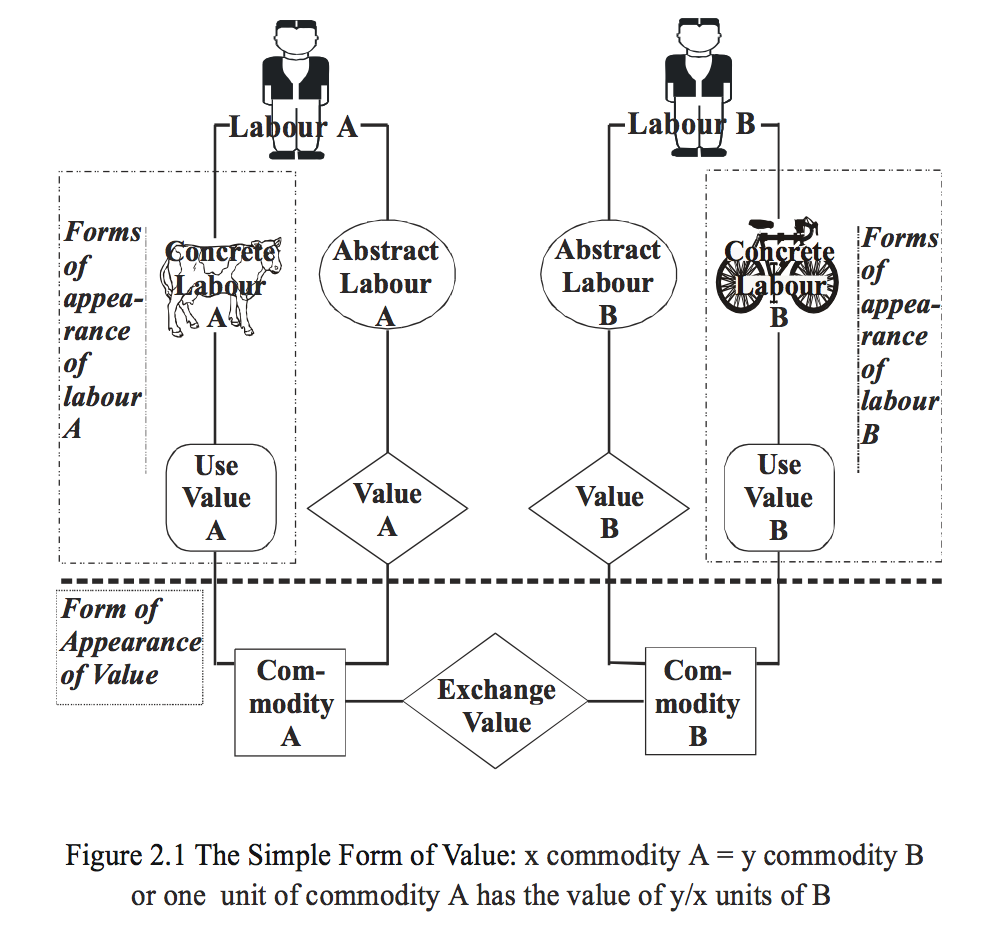

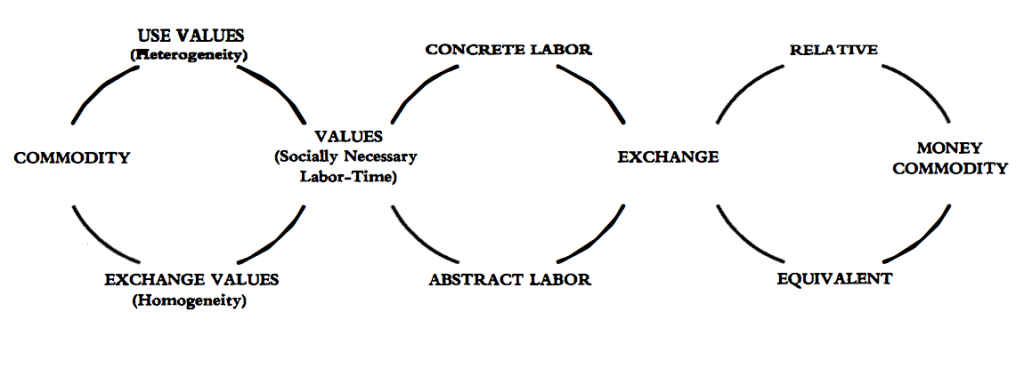

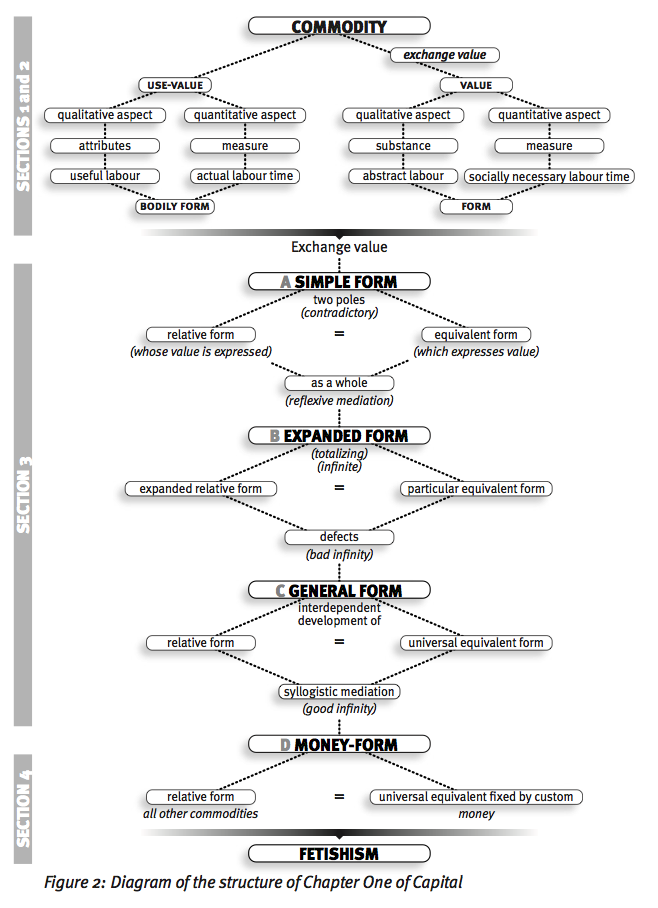

We are calling for papers that acknowledge the foundational work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels for labor theory and engage closely and critically with the critique of political economy. Marx regarded his discovery of the dual character of labor in capitalism (i.e. concrete and abstract) as one of his most important achievements and “the pivot on which a clear comprehension of political economy turns.” With this in mind, we seek contributions that employ Marx’s and Engels’ critical categories of labor, value, the commodity, capital, etc. in reflexive ways which illuminate the role and character of academic labor today and how its existing form might be, according to Marx, abolished, transcended and overcome (aufheben).

Contributions:

- A variety of forms and approaches, demonstrating a close engagement with Marx’s theory and method: Theoretical critiques, case studies, historical analyses, (auto-)ethnographies, essays, and narratives are all welcome. Contributors from all academic disciplines are encouraged.

- Any reasonable length will be considered. Where appropriate they should adopt a consistent style (e.g. Chicago, Harvard, MLA, APA).

- Will be Refereed.

- Contributions and questions should be sent to:

Joss Winn (jwinn@lincoln.ac.uk) and Karen Gregory (kgregory@ccny.cuny.edu)

Publication timetable

- Fully referenced ABSTRACTS by 1st February 2015

- Authors notified by 1st March 2015

- Deadline for full contributions: 1st September 2015

- Authors notified of initial reviews by 1st November 2015

- Revised papers due: 10th January 2016

- Publication date: March 2016.

Possible themes that contributions may address include, but are not limited to:

| The Promise of Autonomy and The Nature of Academic “Time”The Laboring “Academic” Body

Technology and Circuits of Value Production Managerial Labor and Productions of Surplus Markets of Value: Debt, Data, and Student Production The Emotional Labor of Restructuring: Alt-Ac Careers and Contingent Labor The Labor of Solidarity and the Future of Organization Learning to Labor: Structures of Academic Authority and Reproduction Teaching, Learning, and the Commodity-Form The Business of Higher Education and Fictitious Capital |

The Pedagogical Labor of Anti-RacismProduction and Consumption: The Academic Labor of Students

The Division of Labor In Higher Education Hidden Abodes of Academic Production The Formal and Real Subsumption of the University Alienation, Abstraction and Labor Inside the University Gender, Race, and Academic Wages New Geographies of Academic Labor and Academic Markets The University, the State and Money: Forms of the Capital Relation New Critical Historical Approaches to the Study of Academic Labor |

About the Editors:

Karen Gregory

kgregory@ccny.cuny.edu @claudikincaid

Karen Gregory is lecturer in Sociology at the Center for Worker Education/Division of Interdisciplinary Studies at the City College of New York, where she heads the CCNY City Lab. She is an ethnographer and theory-building scholar whose research focuses on the entanglement of contemporary spirituality, labor precarity, and entrepreneurialism, with an emphasis on the role of the laboring body. Karen co-founded the CUNY Digital Labor Working Group and her work has been published in Women’s Studies Quarterly, Women and Performance, The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, and Contexts.

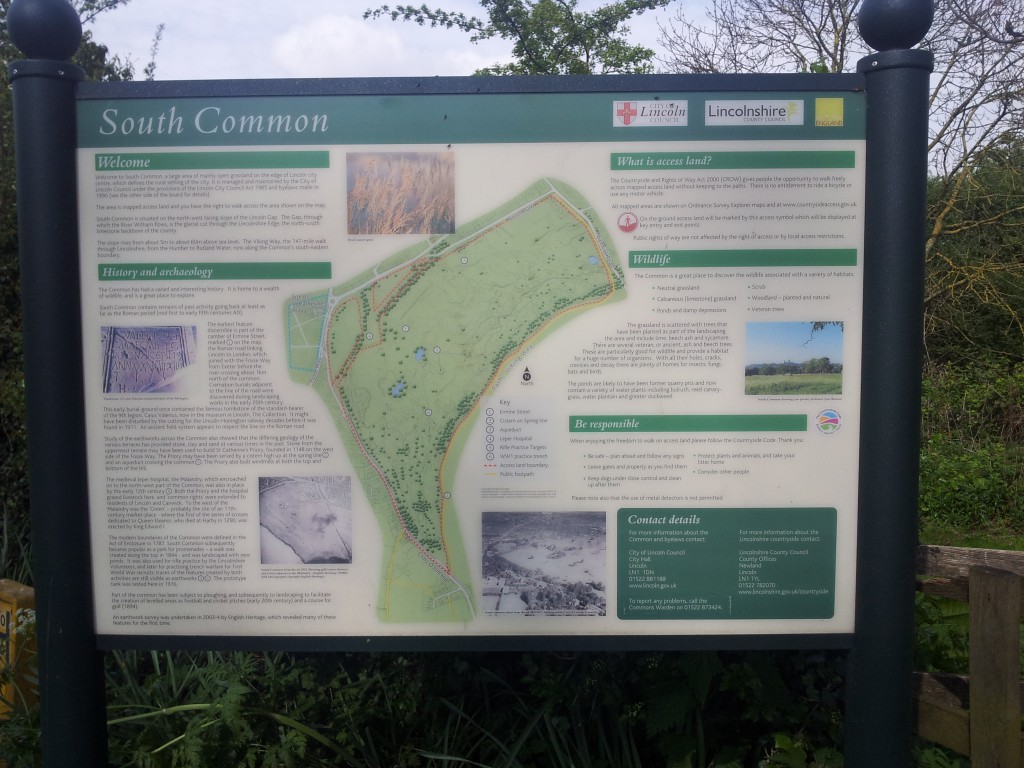

Joss Winn

Joss Winn is a senior lecturer in the School of Education at the University of Lincoln, UK. His research extends broadly to a critique of the political economy of higher education. Currently, his writing and teaching is focused on the history and political economy of science and technology in higher education, its affordances for and impact on academic labor, and the way by which academics can control the means of knowledge production through co-operative and ultimately post-capitalist forms of work and democracy. His article, Writing About Academic Labor, is published in Workplace 25, 1-15.