Below are my notes for a keynote talk at the Reimagining the University [pdf] conference, University of Gloucester.

Thank you for inviting me here today to contribute to what is clearly a growing desire to fundamentally rethink the idea, social purpose and institutional form of the university. This is not the first, nor will it be the last time when academics and students have come together to ‘reimagine the university’. Only two weeks ago, the Scottish unions also held a ‘Reimagining the University‘ [pdf] conference where my colleague from Lincoln, Prof. Mike Neary, was speaking.

I was told that there is a much stronger sense of resistance in Scotland to the changes they see being undemocratically imposed in England and more opportunity for dialogue between the unions, academics, students and policy-makers. We only have to look to Scotland to see that the conditions we face in England are not inevitable. That there is some kind of alternative. More so, if we look to continental Europe where recently all German universities removed their tuitions fees. Denmark, Sweden and Finland do not charge fees either. However, my talk today is not about fees, but about something that I think is more fundamental than how money circulates in our sector.

I was told that there is a much stronger sense of resistance in Scotland to the changes they see being undemocratically imposed in England and more opportunity for dialogue between the unions, academics, students and policy-makers. We only have to look to Scotland to see that the conditions we face in England are not inevitable. That there is some kind of alternative. More so, if we look to continental Europe where recently all German universities removed their tuitions fees. Denmark, Sweden and Finland do not charge fees either. However, my talk today is not about fees, but about something that I think is more fundamental than how money circulates in our sector.

I want to begin by looking back to an earlier conference to ‘Reimagine the University‘, organised this time by students at the University of Leeds in November 2010, shortly after the first of the recent student protests.

I was there on the third day, scheduled to talk about a new model of free, co-operative higher education called the Social Science Centre.

The conference organisers stated that

“It is clear that the university system is bankrupt and in need of profound change, but no-one can see an alternative, a solution, a way out. We need to resist the threatened cuts and the ongoing onslaught on education – but we also need a transformation.”

The conference was both an act of resistance to the recent Browne report that indicated the rise in tuition fees, and also an act of solidary, as students and their teachers walked out of their classes and occupied a central lecture theatre. You’ll understand that the atmosphere at that time was both intense and joyful. Perhaps some of you were there. Across the country, students were occupying their universities, and by doing so were making a direct claim on the property of the institution, rather than walking away from it. They stated:

“We don’t want to defend the university, we want to transform it!”

This is something we need to consider today. What is the relationship between resistance and reimagining? What are we resisting exactly? How can we transform the university through its re-imagination?

Again, my colleague Mike Neary, who always seems to have the foresight to arrive at the scene before I do, had spoken on the previous day of the Leeds occupation about Student as Producer, a project that ran at Lincoln from 2010-2013.

Again, my colleague Mike Neary, who always seems to have the foresight to arrive at the scene before I do, had spoken on the previous day of the Leeds occupation about Student as Producer, a project that ran at Lincoln from 2010-2013.

I’d like to use the remainder of my time in front of you to talk about the relationship between Student as Producer, the Social Science Centre, and most recently, the idea of a co-operative university, and in doing so, to offer some ideas about different routes of resistance and transformation.

And to frame these related projects, I’d like you to think about our collective work as being ‘in, against and beyond’ the university.

Or, if you prefer, work that has as its objective, ‘conversion, dissolution and creation’.

Student as Producer is the teaching and learning strategy for the University of Lincoln. It is a model for teaching and learning based in part on the arguments made by Walter Benjamin in his essays, ‘The Life of Students’ (1915) and ‘Author as Producer’ (1934). In The Life of Students, he writes that

“The organisation of the university has ceased to be grounded in the productivity of its students, as its founders envisaged. They thought of students as teachers and learners at the same time; as teachers because productivity implies complete autonomy, with their minds fixed on science instead of the instructors’ personality.” (Benjamin 1915: 42)

Later, in Author as Producer, he writes,

“[For]… the author who has reflected deeply on the conditions of present day production … His work will never be merely work on products but always, at the same time, work on the means of production. In other words his products must have, over and above their character as works, an organising function.” (Benjamin 1934: 777)

Student as Producer has closed the 19 year gap between these two essays, and argues that

“it is possible to apply Benjamin’s thinking to the contemporary university by applying it to the dichotomous relationship between teaching and research, as embodied in the student and the teacher… to reinvent the relationship between teacher and student, so that the student is not simply consuming knowledge that is transmitted to them but becomes actively engaged in the production of knowledge with academic content and value.” (Neary 2008: 8)

And this is what Student as Producer has aimed to do, inside the University of Lincoln, across the whole institution. Crucially, we have gone to the bureaucratic centre of the university. In every programme and module validation, academics and students are asked to consider how their work could incorporate greater collaboration between students and teachers through the principle of research-engaged teaching and learning. Furthermore, numerous grants are provided to students and staff to support real collaborative research projects outside of the classroom. Out of this climate there is now a Student Engagement team, led by Dan Derricott, a recent graduate and ex-Vice President of the Student Union. Earlier this year, the Lincoln Student Union presented Mike Neary with a lifetime membership in recognition of the work he has lead on Student as Producer.

To what extent we’ve achieved Benjamin’s, and frankly our own, revolutionary ambitions is of course questionable but its impact both inside and outside the institution is undeniable. Yet we must recognise that over time, the subversive, radical language of avant-garde Marxists such as Benjamin has itself been subverted and expressed in the more familiar language of consumption and marketisation, such that it is now common to hear across the sector of ‘Students as Partners‘ and ‘Student as Change Agents‘.

Like all other institutions in the UK that are permitted to hold the title of ‘university’, Lincoln operates within an environment regulated by the State, which increasingly aims to financialise our institutions through coerced competition. It is no longer sufficient to conceive of our universities simply as sites of knowledge production as Benjamin might have. They are now, as Andrew McGettigan’s excellent work informs us, sites of financial speculation. When Benjamin demands that we reflect deeply on the conditions of present day production and its organising function, we must acknowledge that these conditions are fabricated out of fictitious capital, fiat money, and absurd sounding financial instruments such as the “synthetic hedge“, which refers to the use of public funding to guarantee returns to private investment.

So, I put to you that Student as Producer can be seen in terms of a large scale institutional project that has operated inside the university, grounded in social theory that is against what the university has become. It has offered a framework to students and academics for the conversion of the university into an institution grounded in a theory of co-operative knowledge production which recognises that the organising principle of wage work and private property still exists at the heart of the capitalist university, despite the instruments of fictitious finance being constantly employed to conceal the crisis that is capitalism.

More than this, in its most subversive moments, Student as Producer has been an attempt by some of us to dissolve the university into a different institutional form based on a social, co-operative endeavour between academics and students. An endeavour which, as Vygotsky recognised, is not aimed at teaching students skills for the factory, but rather aimed at them discovering for themselves the processes of knowledge production, within which they will find their own place and meaning.

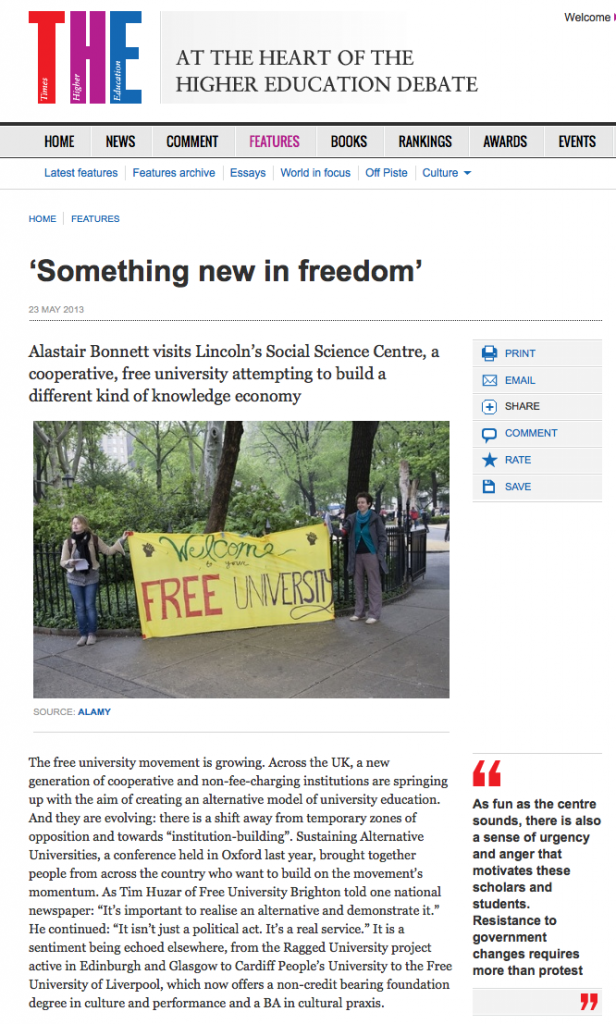

As I mentioned earlier, I was at the Leeds Reimagine the University conference to talk about the Social Science Centre, an initiative which has developed alongside Student as Producer, but outside the university.

In November 2010, the Social Science Centre was little more than an idea that we had written up and were beginning to share with friends and colleagues. It was appropriate that the SSC had its first public outing at the Leeds conference because of the work that Paul Chatterton and Stuart Hodkinson at Leeds had done on autonomous social centres.

Their ESRC-funded research project had revealed to us a network of inspiring autonomous social centres across the UK and Europe, which acted as hubs of resistance to the privatisation of public spaces, such as universities. We saw how these co-operatively run Centres collectively broaden and strengthen the efforts of existing social movements by providing space and resource for the practice of different forms of social relations, not based on wage work and private property but instead on mutual aid and the construction of a social commons. Modelled on the social centres, we wanted the Social Science Centre to provide a space for higher education and for developing our work on Student as Producer in ways that were impossible within a mainstream university.

Their ESRC-funded research project had revealed to us a network of inspiring autonomous social centres across the UK and Europe, which acted as hubs of resistance to the privatisation of public spaces, such as universities. We saw how these co-operatively run Centres collectively broaden and strengthen the efforts of existing social movements by providing space and resource for the practice of different forms of social relations, not based on wage work and private property but instead on mutual aid and the construction of a social commons. Modelled on the social centres, we wanted the Social Science Centre to provide a space for higher education and for developing our work on Student as Producer in ways that were impossible within a mainstream university.

With the constitution of the Social Science Centre as an autonomous co-operative in May 2011, and having no formal relationship to any university, we were able to take Student as Producer outside the walls of the university and with it reconceive higher education itself.

And this is a distinction I want to underline, one that I think we sometimes forget:

Higher education and universities are not synonymous. Universities represent the existing, historical institutional form of higher education, but in our efforts to reimagine the university, we need to extend our work to reimagining the social form of higher education.

That is what the Social Science Centre is for. It is a laboratory for experiments in higher education. It is a model that we think could be replicated by other people. It is not and never has been an alternative to everything that the modern entrepreneurial university seems compelled to do. How could it possibly be compared to the University of Gloucester, Leeds, Lincoln, Oxford? Yet what we can say is that it does provide an alternative to individuals who desire a higher education at the equivalent level to that found inside a university if they wish, with a progressive model of teaching and learning which is reflected in our constitution that insists all members, or ‘scholars’ as we call ourselves, have an equal say in the running of the co-operative. Rather than make the distinction between academics and students, we recognise that we all have much to learn from each other.

And what exactly, I am often asked, is the Social Science Centre?

In a recent collectively authored article in Radical Philosophy, we state that:

“The Social Science Centre (SSC) organises free higher education in Lincoln and is run by its members. The SSC is a co-operative and was formally constituted in May 2011 with help from the local Co-operative Development Agency. There is no fee for learning or teaching, but most members voluntarily contribute to the Centre either financially or with their time. No one at the Centre receives a salary and all contributions are used to run the SSC. When students leave the SSC they will receive an award at higher education level. This award will be recognized and validated by the scholars who make up the SSC, as well as by our associate external members – academics around the world who act as our expert reviewers. The SSC has no formal connection with any higher education institution, but attempts to work closely with like-minded organizations in the city. We currently have twenty-five members and are actively recruiting for this year’s programmes.”

With this in mind, I want to move to the final part of my talk about co-operative higher education and, in fact, about the idea of a ‘co-operative university’. It might help to recall an article on financialisation and higher education written by Andrew McGettigan in which he concludes:

“I am frequently asked, ‘what then should be done?’ My answer is that unless academics rouse themselves and contest the general democratic deficit from within their own institutions and unless we have more journalists taking up these themes locally and nationally, then very little can be done. We are on the cusp of something more profound than is indicated by debates around the headline fee level; institutions and the sector could make moves that will be difficult, if not impossible, to undo, whether it is negotiated independence for the elite or shedding charitable status the better to access private finance.”

The democratic deficit that McGettigan highlights is undoubtedly a key issue that any reimagining of the university must address. However, democracy itself is malleable both as a concept and in practice. What does it even mean to practice democracy here in Cheltenham or in the UK, when supranational networks of capital are being formed to effectively control national and international economic processes?

Resistance to the apparent hegemony of neo-liberalisation and the resulting financialisation of the university is not simply a matter of arousing the public through the media and pushing for changes to institutional governance structures, although both of these are necessary.

Resistance so far has largely been left to students to get on with. What seems clear from this is that the wage we receive as academics is a greater form of discipline than the debt held by students.

I have attended a number of conferences in the last four years which in one way or another sought to answer the question: ‘what then should be done?’ and at each one of them I have been left with a sense of helplessness which I know others share, too.

I think that is because to resist the ‘synthetic hedge’ for example, is not a matter of putting it to the vote, for it is an expression of what the Historian Moishe Postone refers to as “abstract historical processes [that] can appear mysterious ‘on the ground’, beyond the ability of local actors to influence, and can generate feelings of powerlessness.” This ‘mystery’, not to be confused with the complexity of some of the financial instruments, is, Postone argues, a form of “misrecognition” related to the tendency to grasp the abstract domination of capital as something concrete, such as ‘neoliberalism’. He argues, and I am inclined to agree, that this tendency “is an expression of a deep and fundamental helplessness, conceptually as well as politically.”

I am not suggesting that resistance is futile – it can be both satisfying and in the short term, effective – but it no longer seems adequate as a conceptual or political approach to making local changes in the face of global capital.

In reimagining the university, I’d like to suggest that we think of ways, not of resisting but rather of overcoming our current historical context and in doing so I want to propose that in addition to democracy, a number of other values can be combined to create a sustained alternative to how we think about the organising principle of wage work and private property in higher education.

In reimagining the university, I’d like to suggest that we think of ways, not of resisting but rather of overcoming our current historical context and in doing so I want to propose that in addition to democracy, a number of other values can be combined to create a sustained alternative to how we think about the organising principle of wage work and private property in higher education.

“Co-operatives are based on the values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity. In the tradition of their founders, co-operative members believe in the ethical values of honesty, openness, social responsibility and caring for others.”

Co-operatives are based on the seven principles of:

1. Voluntary and Open Membership

2. Democratic Member Control

3. Member Economic Participation

4. Autonomy and Independence

5. Education, Training and Information

6. Co-operation among Co-operatives

7. Concern for Community

As with the Social Science Centre,

“a co-operative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise.”

This combination of values and principles does not take a single institutional form but like Student as Producer, offers a framework for reconceiving, or reimagining, our social relations, the meaning of work and the purpose of teaching and learning. It does take real effort though, and none of this will be easy to construct unless is it formed out of a conscious act of solidarity not just among a few individuals, but within the national and international co-operative movement as a whole.

Whether there is the appetite for it, is not yet clear, although something is stirring. 1 In the last three years, there have been meetings and conferences where the idea of co-operative higher education has been discussed; and a recent report by Dan Cook and sponsored by the Co-operative College, was pivotal in framing both the interest from the College and the initial questions one might ask. These questions will no doubt be discussed again at a forthcoming conference on co-operative education, hosted by the Co-operative College.

In a recent paper, I have argued that taken as a whole, efforts around co-operative higher education over the last three years can be understood in terms of the three routes I mentioned at the beginning of this talk: Conversion, dissolution, and creation.

In a recent paper, I have argued that taken as a whole, efforts around co-operative higher education over the last three years can be understood in terms of the three routes I mentioned at the beginning of this talk: Conversion, dissolution, and creation.

By this I mean the wholesale conversion of existing universities to co-operatives; or the gradual and possibly subversive dissolution of university processes into co-operatively governed equivalents; or the creation of new institutional forms of co-operative higher education. The success of each should not be measured against the apparent success of existing mainstream universities, but rather on the participants’ own terms and the type of higher education they need and desire.

At this stage, we should not privilege one route over another nor any single institutional form over another. It is too early to draw lines and there is a need for much more experimentation before the dust settles on what specific social form co-operative higher education might take. For my part, I am interested in drawing from the theory and practice of worker co-operatives, which Marx recognised as ‘attacking the groundwork’ of capitalism due to its unique configuration of worker democracy, social property and the absence of wage labour.

Co-operativism is no panacea to the abstract domination of global capital and certainly not our end goal, but rather a historically and politically constituted framework that places an emphasis on values and principles that cross the divisions of public and private, wage work and unemployment, teacher and student, teaching and learning. Whatever forms it takes, one thing is for sure: we must not end up with more of the same.