A paper for ‘Friction: An interdisciplinary conference on technology & resistance‘, University of Nottingham, Thursday 8th May & Friday 9th May.

In a paper published last year, I argued for a different way of understanding the emergence of hacker culture. (Winn 2013) In doing so, I outlined an account of ‘the university’ as an institution that provided the material and subsequent intellectual conditions that early hackers were drawn to and in which they worked.

The key point I tried to make was that hacking was originally a form of academic labour that emerged out of the intensification and valorisation of scientific research within the institutional context of the university. The reproduction of hacking as a form of academic labour took place over many decades as academics and their institutions shifted from an ideal of unproductive, communal science to a more productive, entrepreneurial approach to the production of knowledge.

As such, I view hacking as a peculiar, historically situated form of labour that arose out of friction in the academy: vocation vs. profession; teaching vs. research; basic vs. applied research; research vs. development; private vs. public; war vs. peace; institutional autonomy vs. state dependence; scientific communalism vs. intellectual property; individualism vs. co-operation.

A question I have for you today is whether hacking in the university is still a possibility? Can a university contain (i.e. intellectually, politically, practically) a hackerspace? Can a university be a hackerspace? If so, what does it look like? How would it work? I am trying to work through these questions at the moment with colleagues at the University of Lincoln. The name I have given to this emerging project is ‘The university as a hackerspace’ and it has grown out of an existing pedagogical and political project called ‘Student as Producer.’ It is also one of four agreed areas of work in a new ‘digital education’ strategy at Lincoln.

More broadly, our project asks “how do we reproduce the university as a critical, social project?”

STUDENT AS PRODUCER

Student as Producer is the University of Lincoln’s teaching and learning strategy and is in part derived from the work of avant-garde Marxists like Lev Vygotsky, and Walter Benjamin, who gave a lecture in 1934 known as ‘The Author as Producer’. Benjamin was concerned with the relationship between authors and their readers and how to actively intervene in “the living context of social relations” so as to create progressive social transformation:

“[For]… the author who has reflected deeply on the conditions of present day production … His work will never be merely work on products but always, at the same time, work on the means of production. In other words his products must have, over and above their character as works, an organising function.” (Benjamin 2005: 777)

Student as Producer was also an HEA-funded project that we completed recently, led by my colleague Prof. Mike Neary, who was the Dean of Teaching and Learning from 2007-14. Last year, the QAA commended the university for Student as Producer. Mike Neary and another colleague, Sam Williams, came to talk about Student as Producer here at the University of Nottingham just a couple of weeks ago and I’m told it was very well received.

Student as Producer at Lincoln is a university-wide initiative, which aims to construct a productive and progressive pedagogical framework through a re-engineering of the relationship between research and teaching and a reappraisal of the relationship between academics and students. Research-engaged teaching and learning is now “an institutional priority at the University of Lincoln, making it the dominant paradigm for all aspects of curriculum design and delivery, and the central pedagogical principle that informs other aspects of the University’s strategic planning.” (HEA 2010)

In an early book chapter setting out the rationale for Student as Producer, Mike and I argued that:

“The idea of student as producer encourages the development of collaborative relations between student and academic for the production of knowledge. However, if this idea is to connect to the project of refashioning in fundamental ways the nature of the university, then further attention needs to be paid to the framework by which the student as producer contributes towards mass intellectuality. This requires academics and students to do more than simply redesign their curricula, but go further and redesign the organizing principle, (i.e. private property and wage labour), through which academic knowledge is currently being produced.” (Neary & Winn, 2009, 137)

Central to Student as Producer is an attempt to reconfigure the dysfunctional relationship between teaching and research in higher education and a conviction that this can be best achieved by rethinking the relationship between student and academic.

The argument for Student as Producer has been developed through a number of publications which assert that students can and should be producers of their social world by being collaborators in the processes of research, teaching and learning. Student as Producer has a radically democratic agenda, valuing critique, speculative thinking, openness and a form of learning that aims to transform the social context so that students become the subjects rather than objects of history – individuals who make history and personify knowledge. Student as Producer is not simply a project to transform and improve the ‘student experience’ but aspires to a paradigm shift in how knowledge is produced, where the traditional student and teacher roles are ‘interrupted’ through close collaboration, recognizing that both teachers and students have much to learn from each other. Student as Producer aims to ensure that theory and practice are understood as praxis, what Paulo Freire referred to as a process of “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it.” (Freire 2000, 51).

A critical, social and historical understanding of the university and the roles of researcher, teacher and student inform these aspirations and objectives. They draw on radical moments in the history of the university as well as looking forward to possibilities of what the university can become. I think that one such radical moment could be the “software wars” that Richard Stallman has described when he tried desperately to hold together his “commune” in the “Garden of Eden” that was the AI Lab in MIT during the late 1970s. That moment was the genesis of the Free Software movement and the creation of the GPL license, and a time when hacking formally ‘escaped’ the confines of the university.

Student as Producer recognizes that the higher education sector is in a state of crisis, which is reflective of a more general social crisis. At a time when the higher education sector is being privatized and students are expected to assume the role of consumer, Student as Producer aims to provide students with a more critical, more historically and socially informed, experience of university life which extends beyond their formal studies to engage with the role of the university, and therefore their own role, in society. Pedagogically, this is through the idea of ‘excess’ where students are anticipated to become more than just student-consumers during their course of research and study (Neary & Hagyard, 2010). The idea of ‘excess’ is suggestive of a state of abundance (Kay and Mott, 1982), of conditions of non-reciprocity: “from each according to his ability to each according to his needs.” You will have experienced moments of such abundance and non-reciprocity in your own lives: with your lovers, your children, and in the culture of sharing on the web.

Our aim is that through this ‘pedagogy of excess’, the organising principle of university life is redressed, creating a teaching, learning and research environment which promotes the values of experimentation, openness and creativity, engenders equity at the level of academic and student labour and thereby offers an opportunity to reconstruct the student as producer and academic as collaborator. In an anticipated environment where knowledge is free (as in ‘freedom’, if not as in ‘beer’), the roles of the educator and the institution necessarily change. The educator is no longer a delivery vehicle and the institution becomes a landscape for the production and construction of a mass intellect in commons, a porous, networked space of abundance, offering an experience that is in excess of what students might find elsewhere.

In our 2009 book chapter, we specifically drew on the activities of the Free Culture movement as an exemplary model for how the disconnect between research and teaching and the work of academics and students, might be overcome and reorganized around a different conception of work and property, ideas central to the meaning of ‘openness’ or, rather, an ‘academic commons’.

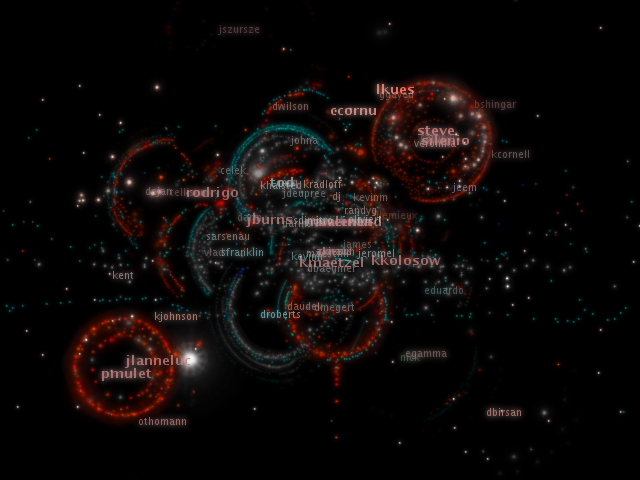

LNCD IS NOT A CENTRAL DEVELOPMENT GROUP

One of the reasons I have come to think about ‘the university as a hackerspace’ is due to what I regard as a failure of my earlier work. It depends on how you regard ‘failure’ – we learned a lot, attracted lots of research funding, and the work was interesting and seemed to interest other people – but it didn’t fully have the effect on the institution that I was hoping for. Between 2009 and 2013, I ran ten grant-funded projects, each of which focused on the theme of ‘openness’ or as I prefer, the ‘academic commons’. This work was consolidated under a group that we called LNCD. LNCD is a recursive acronym and stands for ‘LNCD is Not a Central Development Group’. It was intended to be an open, inclusive group run according to the principles of Student as Producer and open to students and staff from across the university.

With the LNCD group, I acknowledged that the origins of much of our work was in the hacker culture that grew out of MIT, Carnegie Mellon University and University of California, Berkeley in the 1970 and 1980s; the academic culture that developed much of the key technology of today’s Internet.” (Winn and Lockwood 2013) I think that the Free Culture movement in general owes much to its academic origins and can be understood as an exemplar alternative organizing principle that is proliferating in universities in the form of open, networked collaborative initiatives such as Open Access and Open Educational Resources. (Neary and Winn 2009)

“When understood from this point of view, LNCD, as a Student as Producer initiative, is attempting to develop a culture for staff and students based on the key academic values that motivated the early academic hacker culture: autonomy, the sharing of knowledge and creative output, transparency through peer-review, and peer-recognition based on merit.” (Winn and Lockwood 2013)

During this period, we also ran a national student hackathon called DevXS when 180 students from around the country came to Lincoln for two days to “challenge and positively disrupt the research, teaching and learning landscapes of further and higher education.” I’ve written about some of the projects and the hackathon elsewhere (Winn 2012; Winn and Lockwood 2013).

I was always mindful that LNCD should contribute towards the greater strategic priority of Student as Producer. It would do this by helping re-configure the nature of teaching and learning in higher education by encouraging students to become part of the academic project of the University and collaborators with academics in the production of knowledge and meaning. To recall Benjamin’s lecture: for me, LNCD was an attempt to “reflect deeply on the conditions of present day production” in higher education, and “at the same time, work on the means of [knowledge] production” with students and other members of staff.

AN ANTI-DISCIPLINARY RESEARCH DEGREE

The problem with LNCD is that we became regarded as just another research group and did not become the ‘skunkworks’ group for the institution that I hope we would. When JISC, the funder of our projects, ceased to advertise funding calls, there was nothing to fall back on. I was pretty burnt out by that point, too.

As an alternative to what I tried to do through LNCD, we are now working towards the validation in 2015 of a new post-graduate research degree, provisionally titled ‘The university as a hackerspace’. My hope is that as an academic programme with students, it will be more reflective of, and tightly integrated into, the core function and purpose of the university: research-based teaching and learning. I hope this will make it more sustainable and that staff will understand its objectives better than they did LNCD.

It is intended to be Lincoln’s first cross-university, ‘anti-disciplinary’ academic programme. It is intended to act as a focal point for teaching, learning, research and development of new technologies and technology culture. It is not intended to be a degree about ‘educational technology’, but rather a creative, critical research programme that seeks to understand and contribute to the role of technology in education through its wider role in society and culture.

The idea for this Master’s level research programme, is influenced by the rapidly emerging ‘makerspaces’ and ‘hackerspaces’. The programme will seek to learn from, emulate and contribute to what we see happening in hacker/maker/DIY culture: e.g. ‘fablabs’, ‘hacklabs’, and ‘open science’. Research and development outputs from the programme are expected to formally feed back and inform the way that the university invests in, supports and promotes the use of technology for education and research. In this way, the research programme is intended to act, in part, as a ‘skunkworks’ group for the whole institution.

The programme will combine inter-disciplinary research and development, teaching, learning and enterprise, but recognises that those activities are evolving and that hackers, makers and entrepreneurs are developing an alternative educational model that is replacing these functions of the university: the opportunities for learning, collaboration, reputation building/accreditation and access to cheap hardware and software for prototyping ideas, can and are taking place outside universities. However, university culture remains a place where the ‘hacker ethic’ (i.e. collaboration, sharing, respect for good ideas, meritocracy, autonomy, curiosity, fixing things, anti-technological determinism, peer review, perpetual learning, etc.) remains relevant and respected and resources are widespread. (Levy 1984; Himanen 2001)

The degree will be a flexible, research-based, postgraduate programme that is truly interdisciplinary and always experimental in its form and content: A space for learning, critique and innovation, engaging academics and students in the sciences, arts, media and humanities to think deeply about the way technology is used for research, teaching, learning and the wider social good. The programme will create a supportive space for students with different disciplinary backgrounds and interests to work together under the mentorship of university staff. The programme will recognise that both staff and students have much to learn from each other.

QUESTIONS NEEDING ANSWERS

We’re still in the early stages of thinking this through and as you can imagine, it’s throwing up a number of questions.

- Can a university contain (intellectually, politically, practically) a hackerspace?

- Are the two organisational and educational forms compatible?

- Who owns an ‘antidisciplinary’ programme?

- Who benefits from it? How?

- Why would a student enrol?

- How can we involve the local community?

- What is the final award?

- How are contributions (staff time, Schools’ facilities) acknowledged?

- How is the degree structured?

- How many students are required to make this work (i.e. what is the critical size of the ‘collective’)

- What are the administrative constraints and regulatory obligations?

I welcome comments on what we are trying to do and whether you think it is feasible or even desirable. If you know of similar efforts elsewhere, please share them. Thank you.

FURTHER READING

Special Issue of Journal of Peer Production

http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-2/peer-reviewed-papers/

Hackerspaces: The Beginning (book)

http://blog.hackerspaces.org/2011/08/31/hackerspaces-the-beginning-the-book/

Benjamin, Walter (2005) Walter Benjamin: 1931-1934 v. 2, Pt. 2: Selected Writings, Harvard University Press.

Friere, Paulo (2000) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Continuum.

HEA (2010) Student as Producer: Research Engaged Teaching and Learning-An Institutional Strategy http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/projects/detail/ntfs/ntfsprojects_Lincoln10

Himanen, Pekka. 2001. The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age. Vintage.

Kay, Geoffrey and Mott, James (1982) Political Order and the Law of Labour. The MacMillan Press, London.

Levy, Steven.1984. Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Penguin Books.

Neary, Mike and Winn, Joss (2009) The student as producer: reinventing the student experience in higher education. In: The future of higher education: policy, pedagogy and the student experience. Continuum, London, pp. 192-210.

Neary, M. and Hagyard, A. (2010) ‘PedagogyofExcess: AnAlternativePoliticalEconomyofStudentLife’. In: The Marketisation of Higher Education and the Student as Consumer, Routledge, Abingdon, 209-224.

Schrock, Andrew Richard (2014) “Education in Disguise”: Culture of a Hacker and Maker Space http://escholarship.org/uc/item/0js1n1qg

Winn, Joss (2012) Hacking the university. Lincoln’s approach to openness. http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/topics/opentechnologies/openeducation/lincoln-university-summary.aspx

Winn, Joss and Lockwood, Dean (2013) Student as Producer is hacking the university. In: Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age . Routledge.

Winn, Joss (2013) Hacking in the university: contesting the valorisation of academic labour. Triple C : Communication, Capitalism and Critique, 11 (2). pp. 486-503.